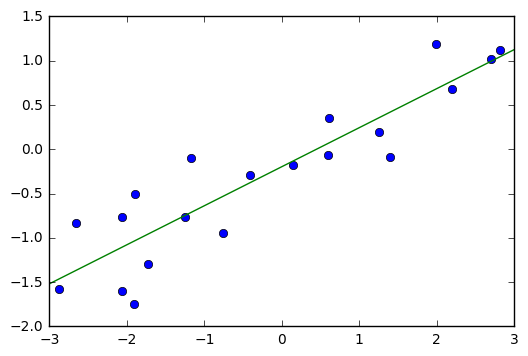

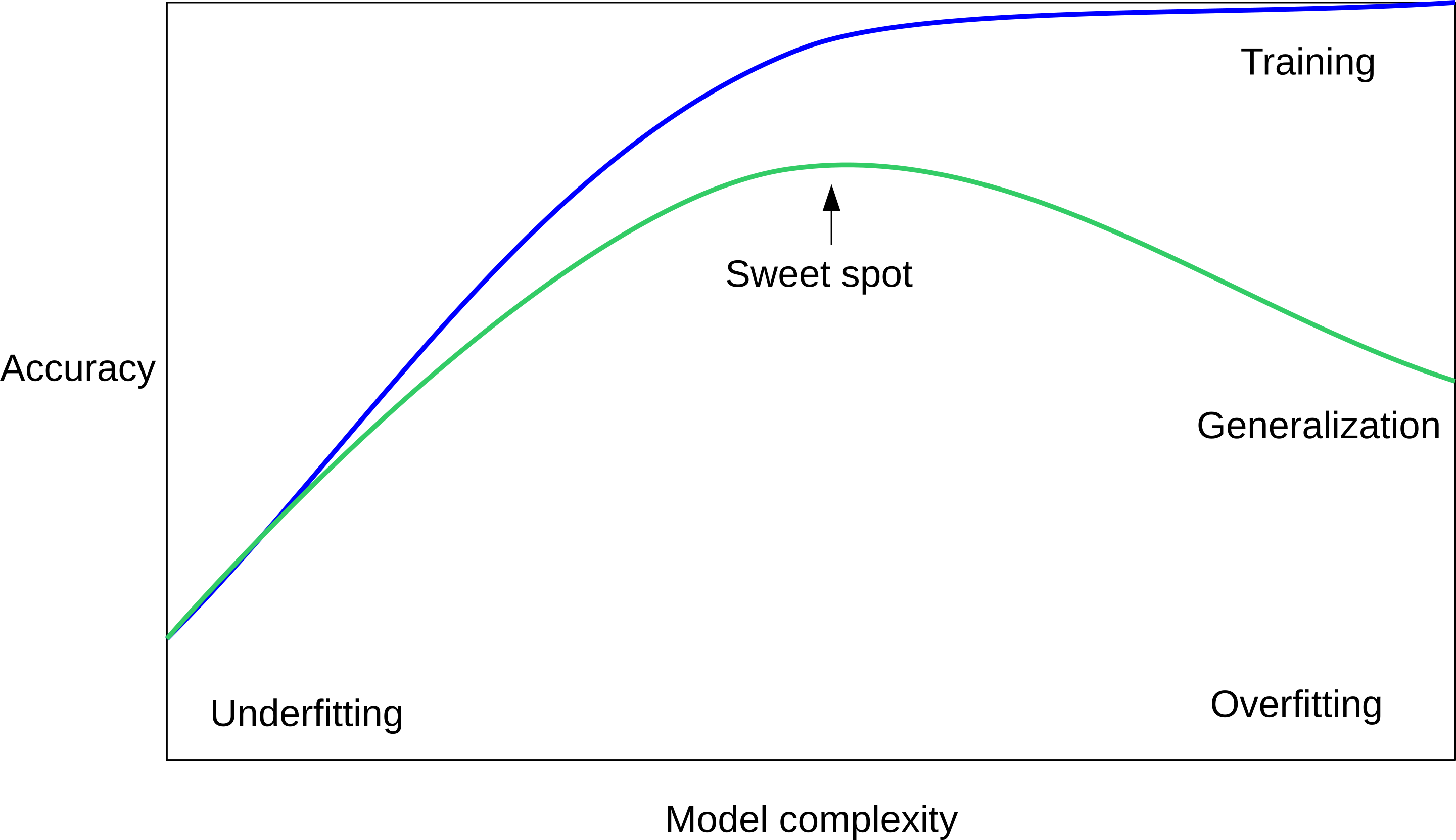

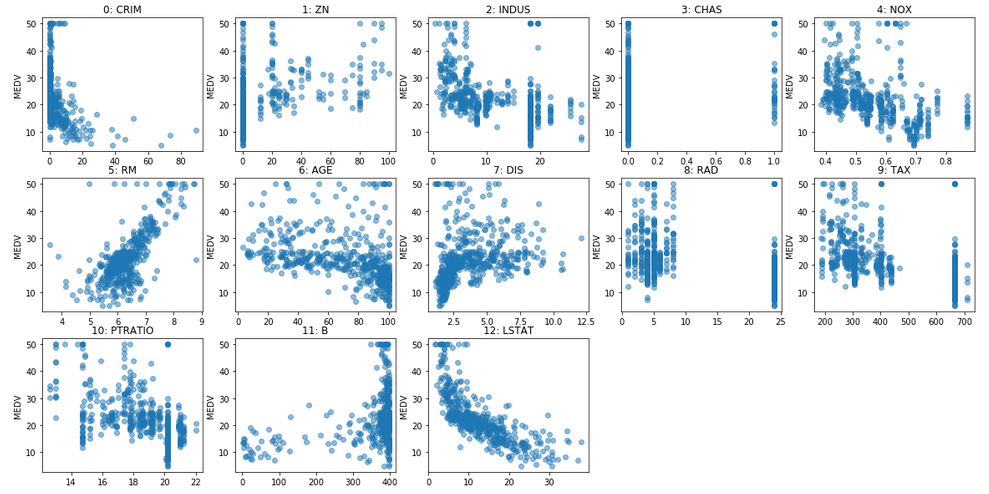

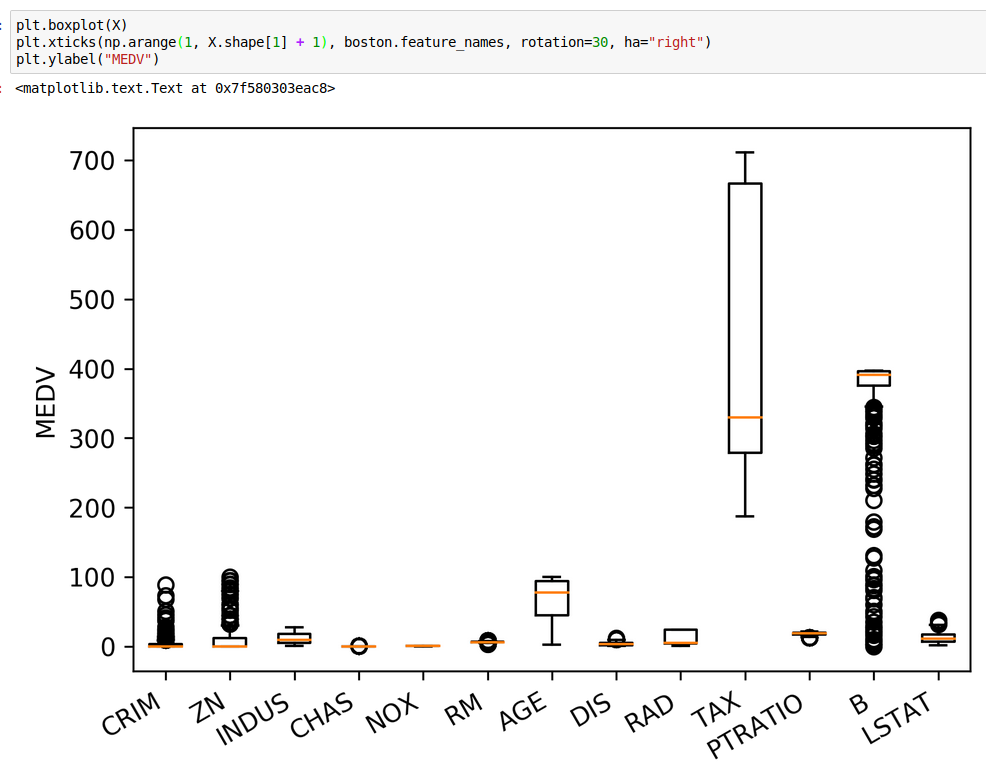

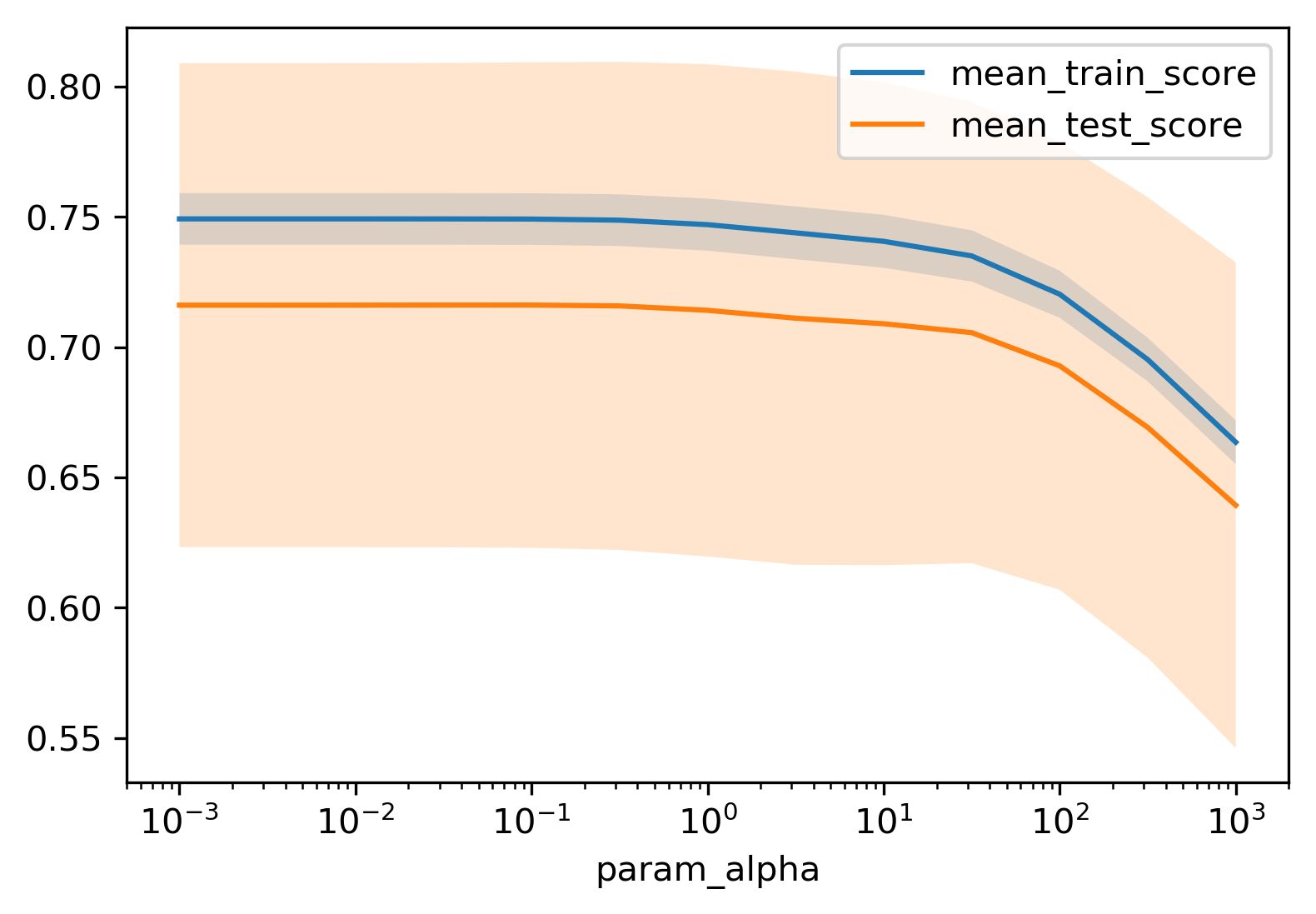

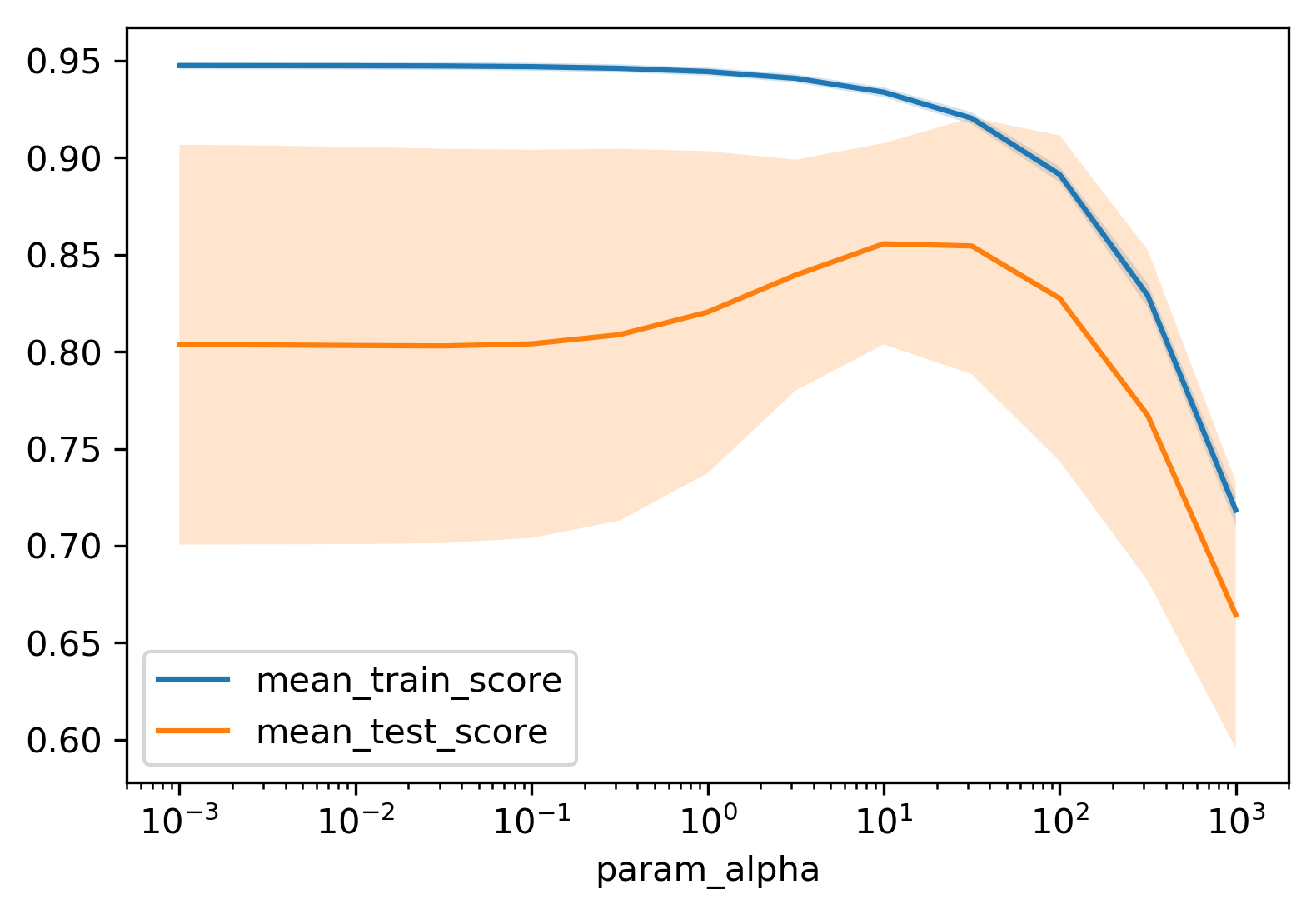

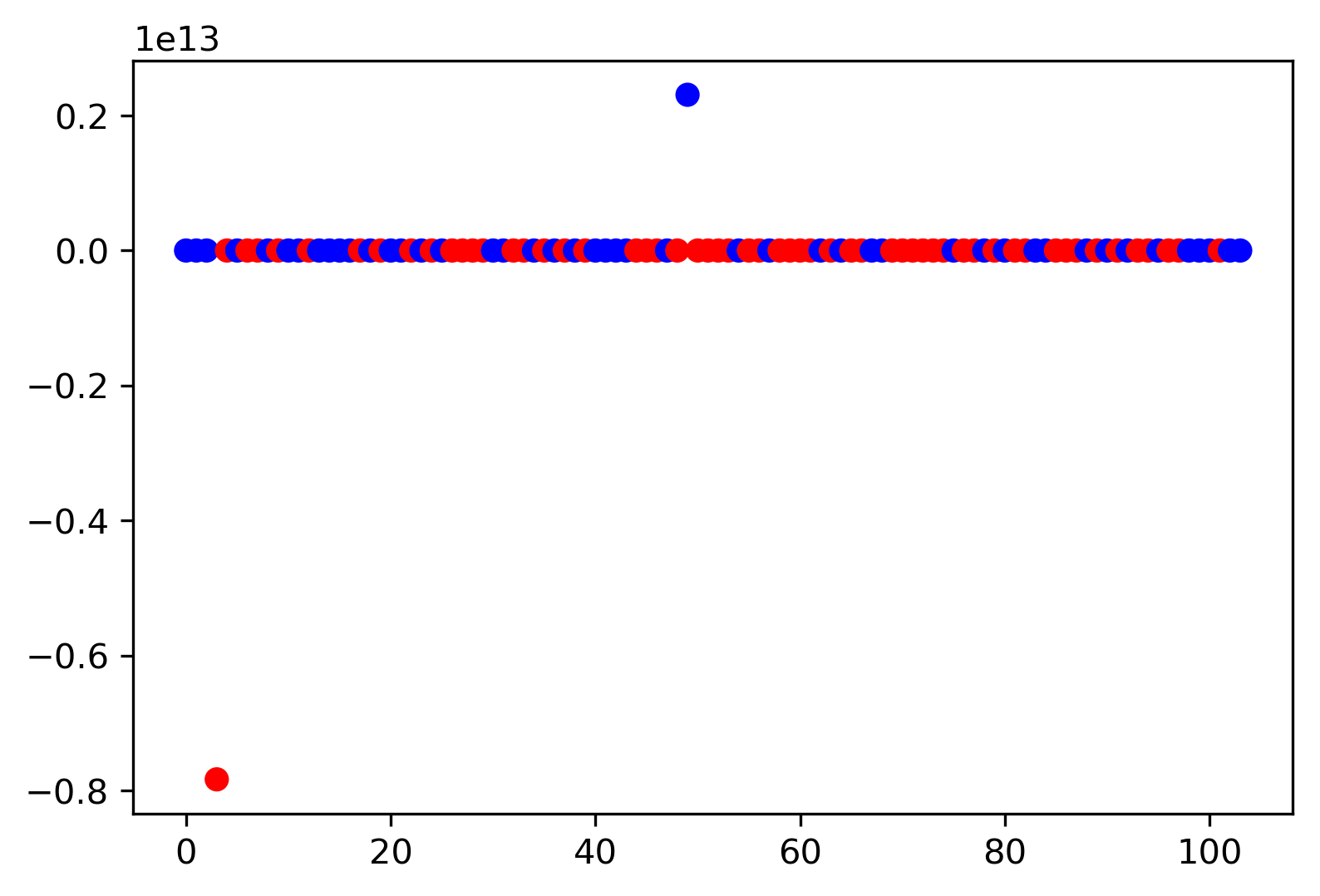

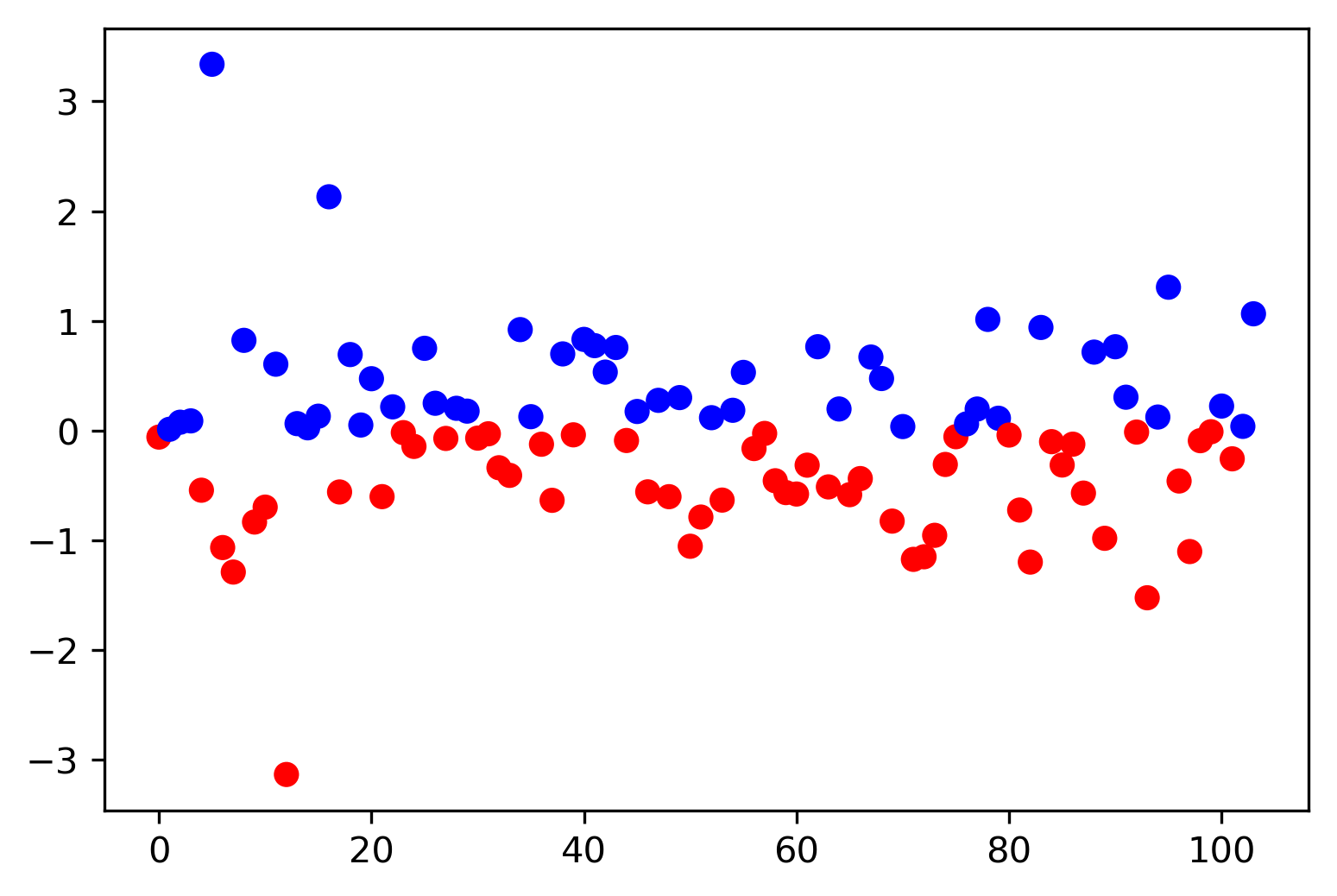

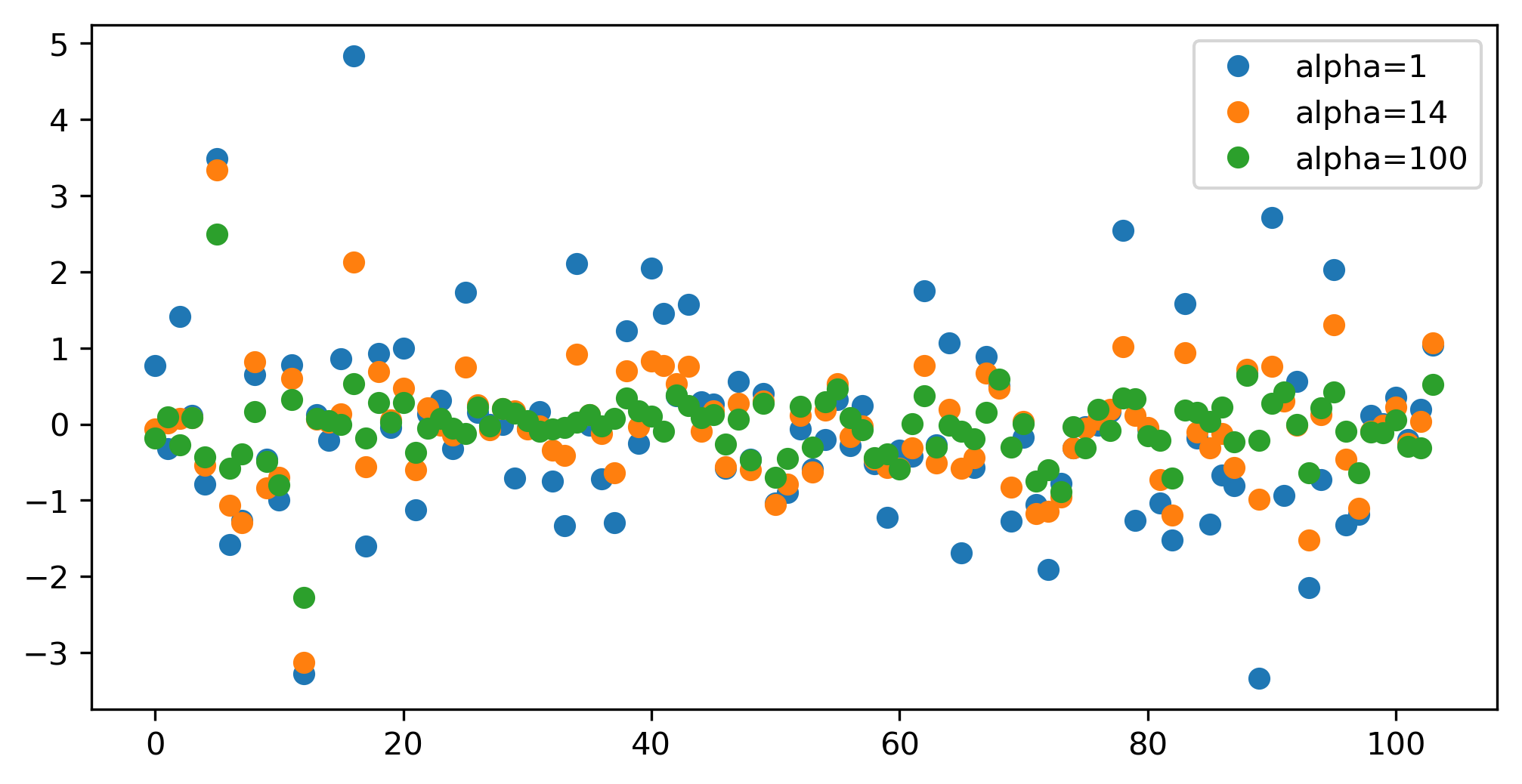

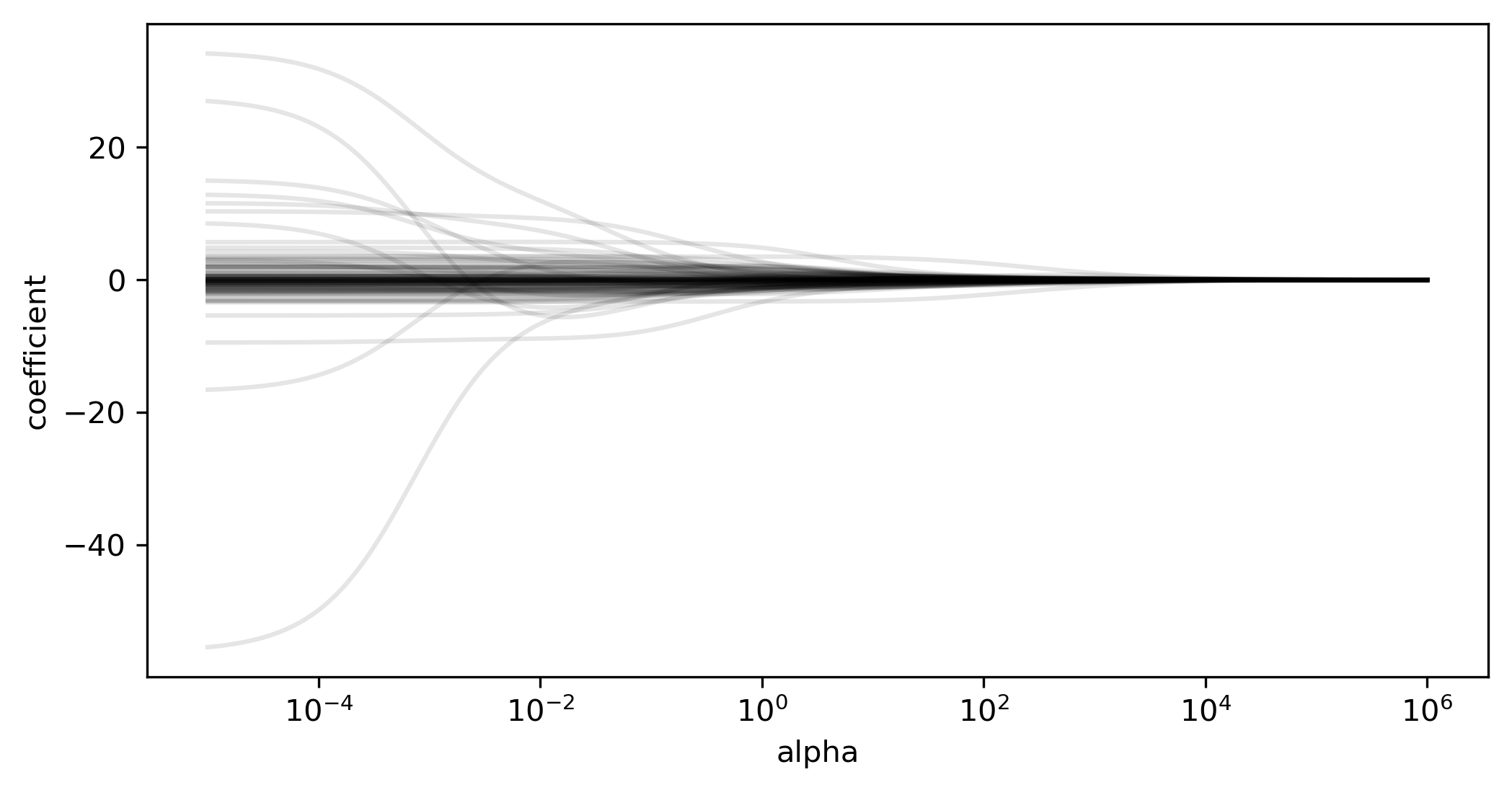

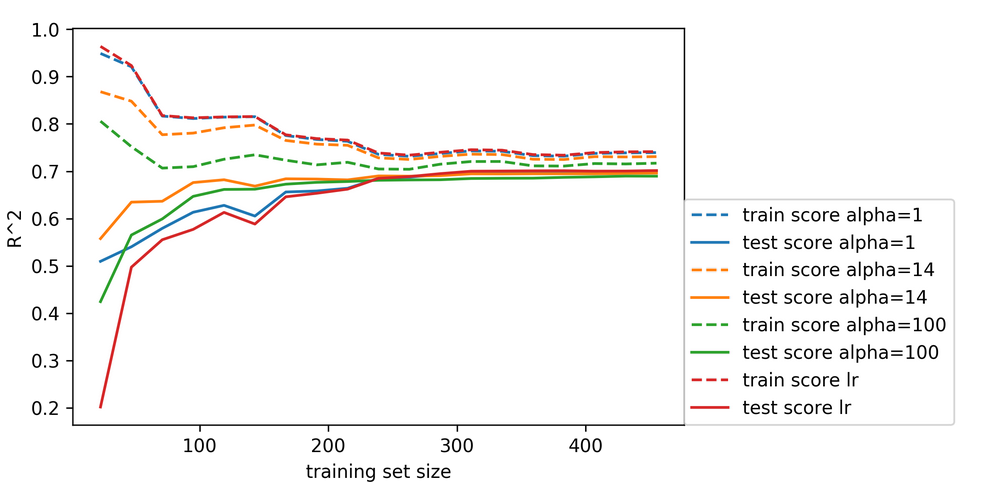

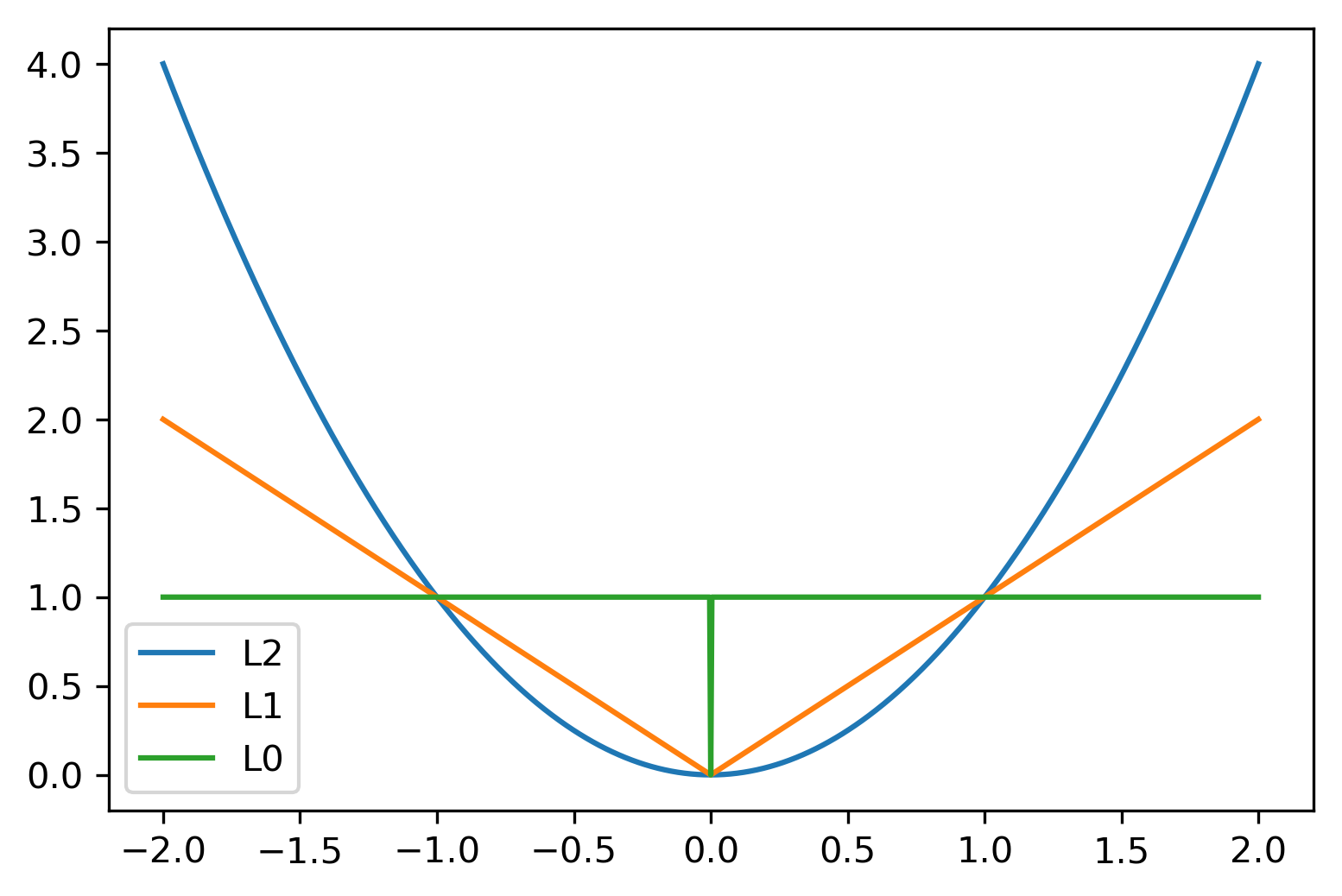

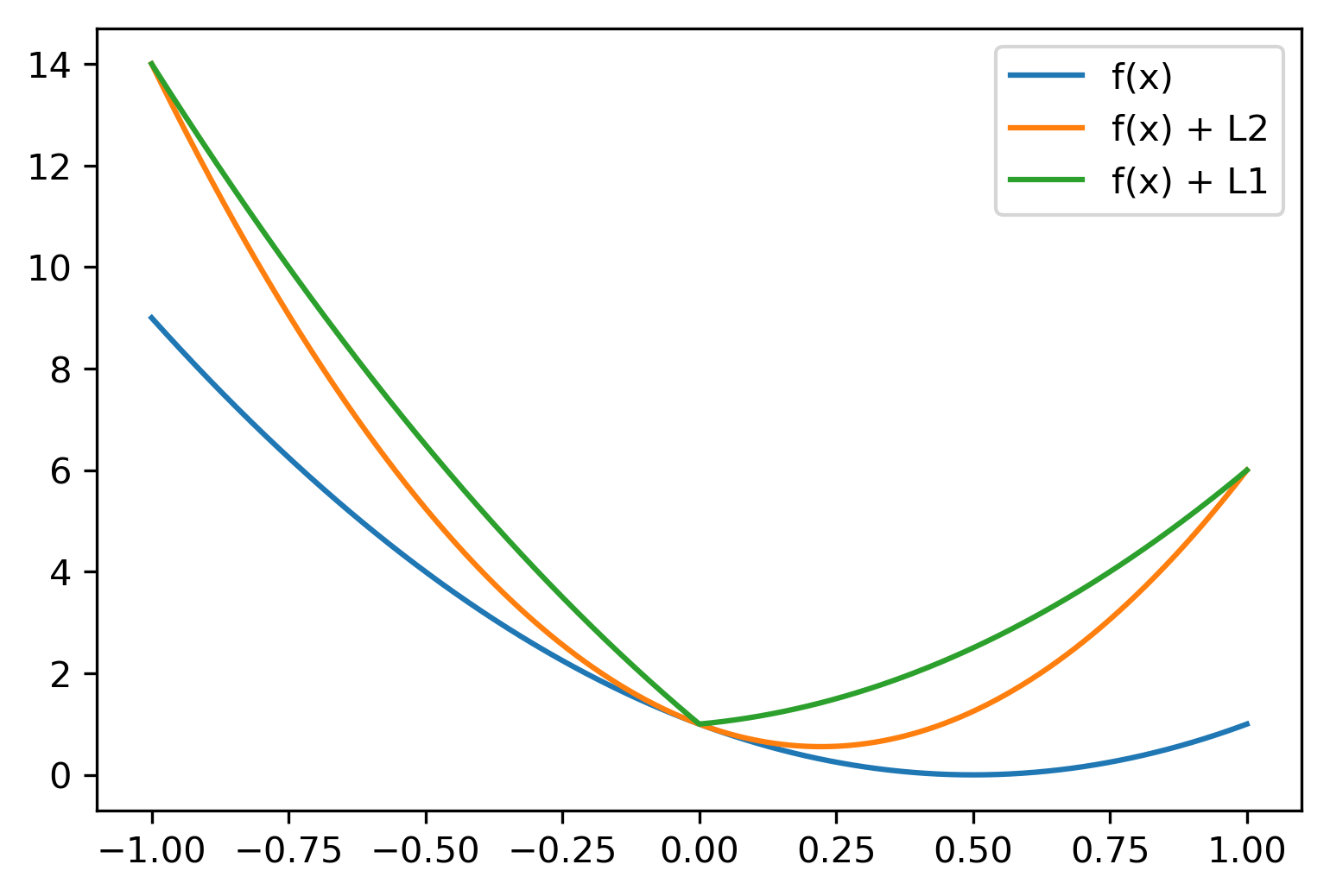

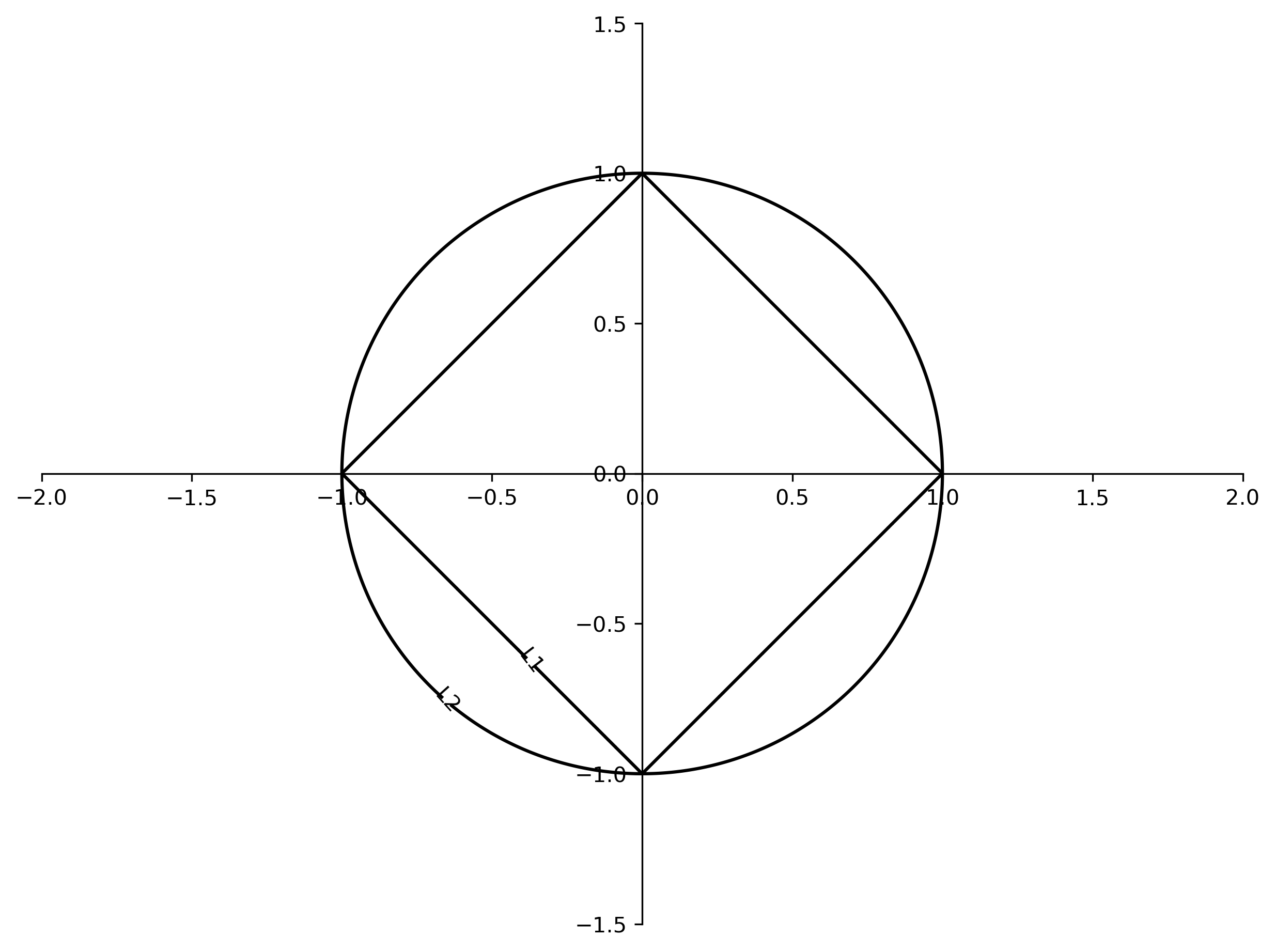

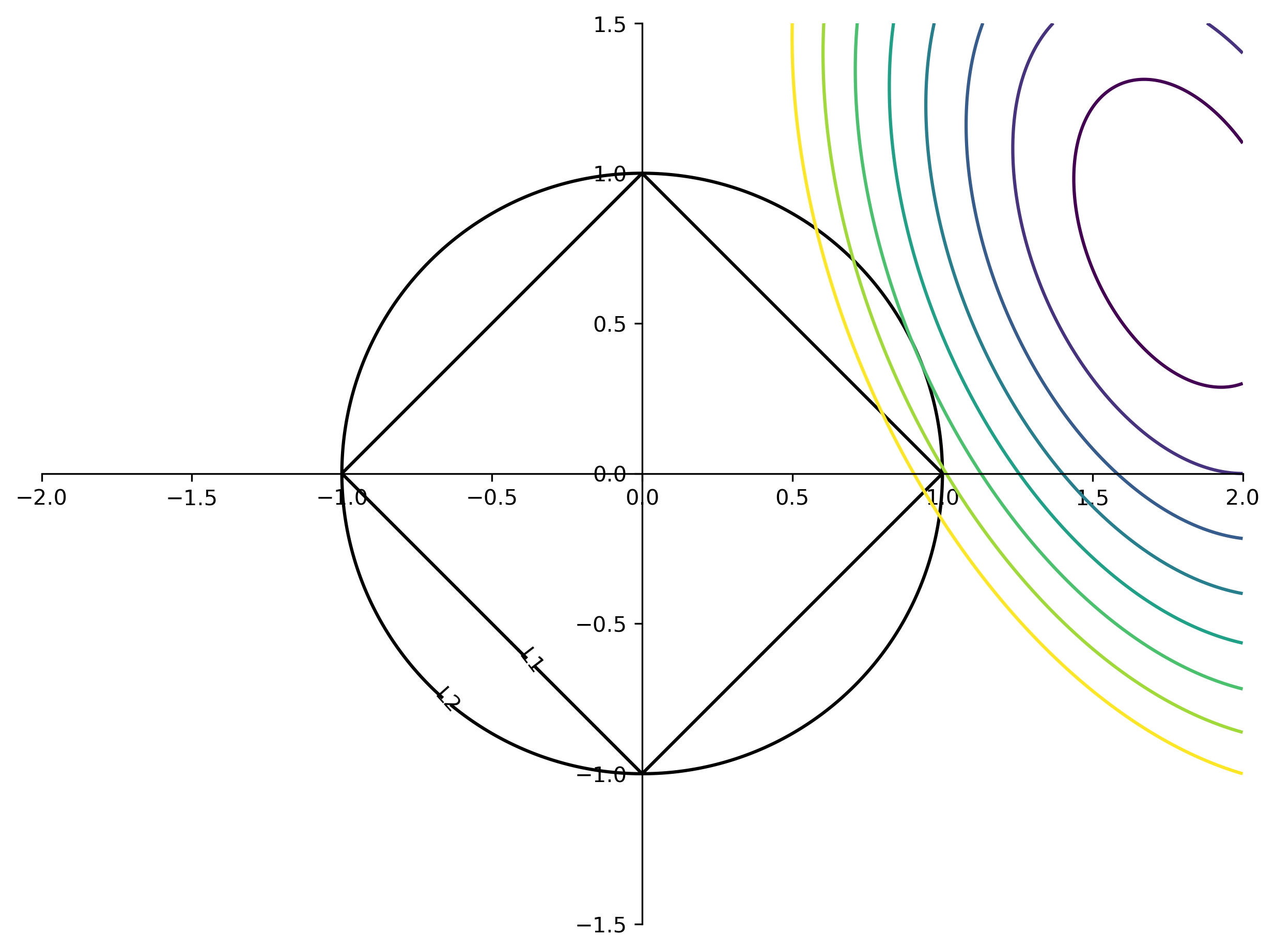

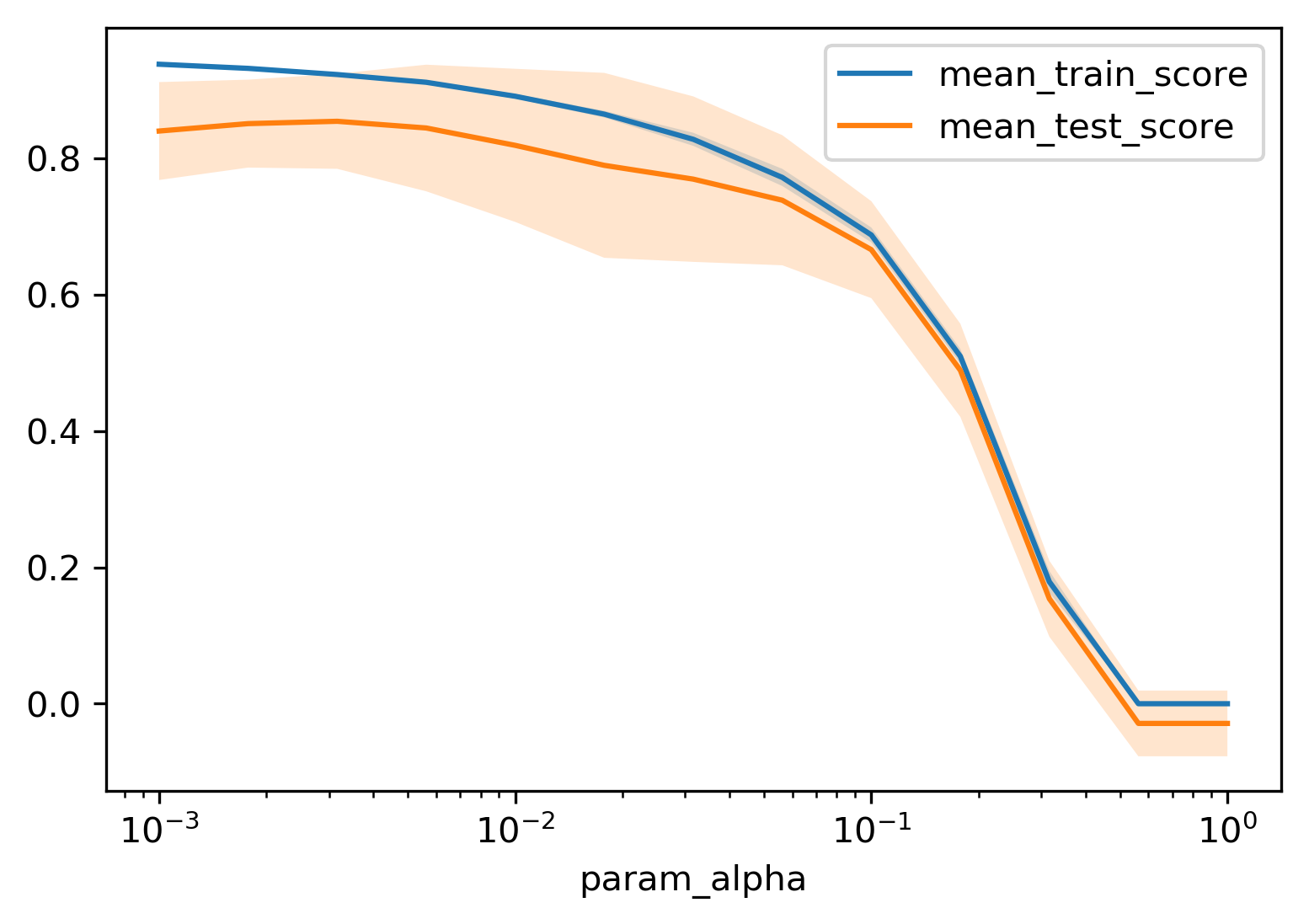

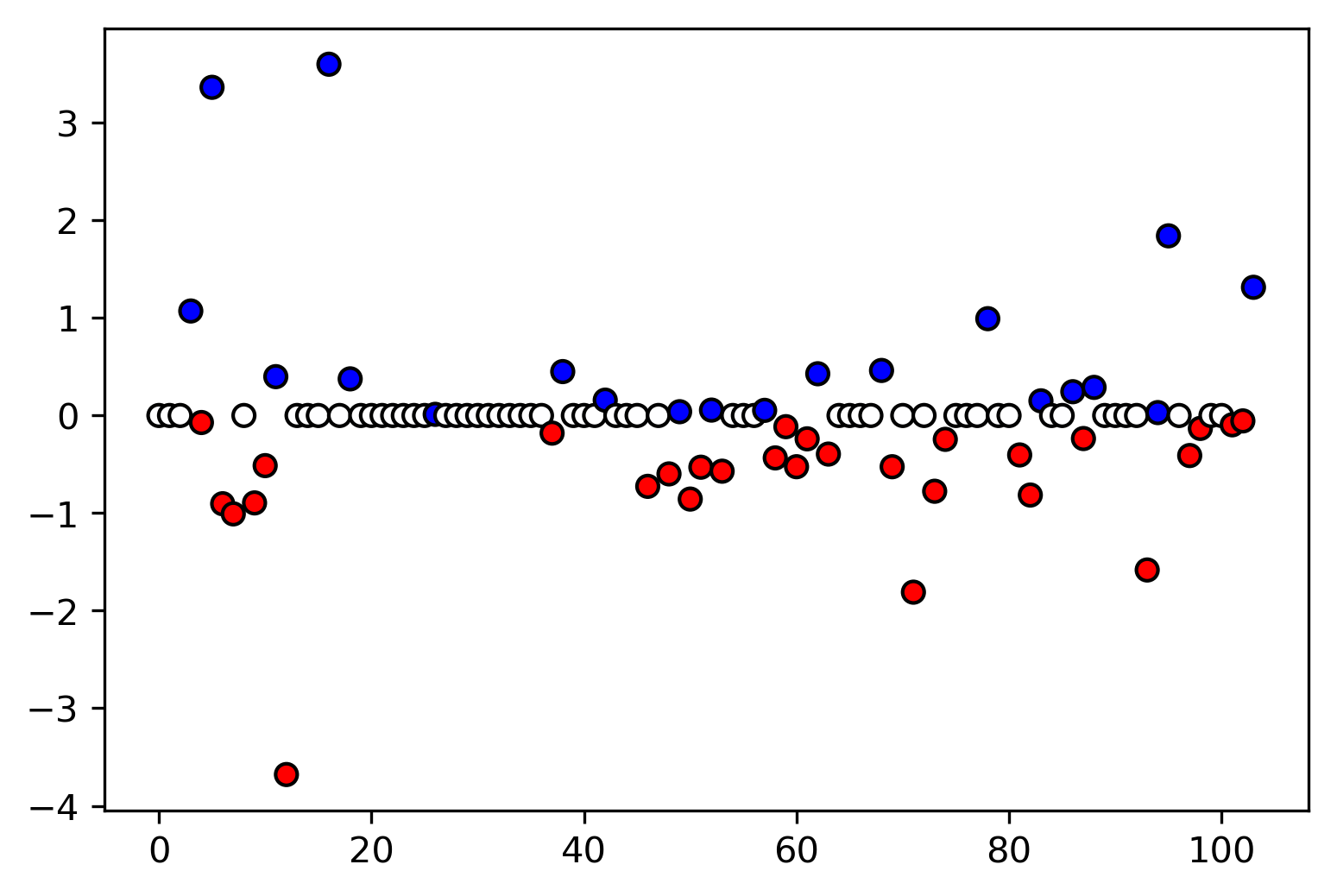

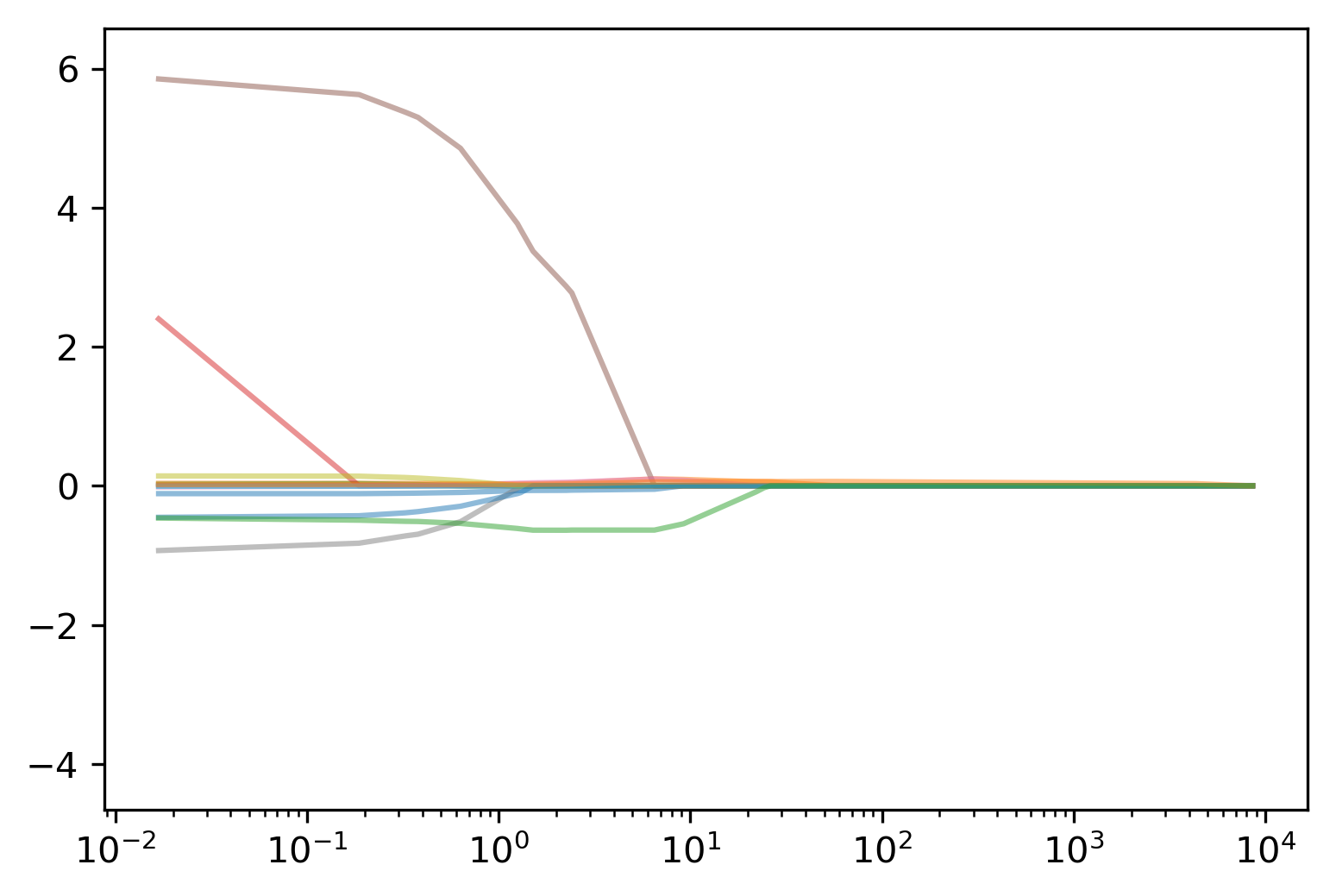

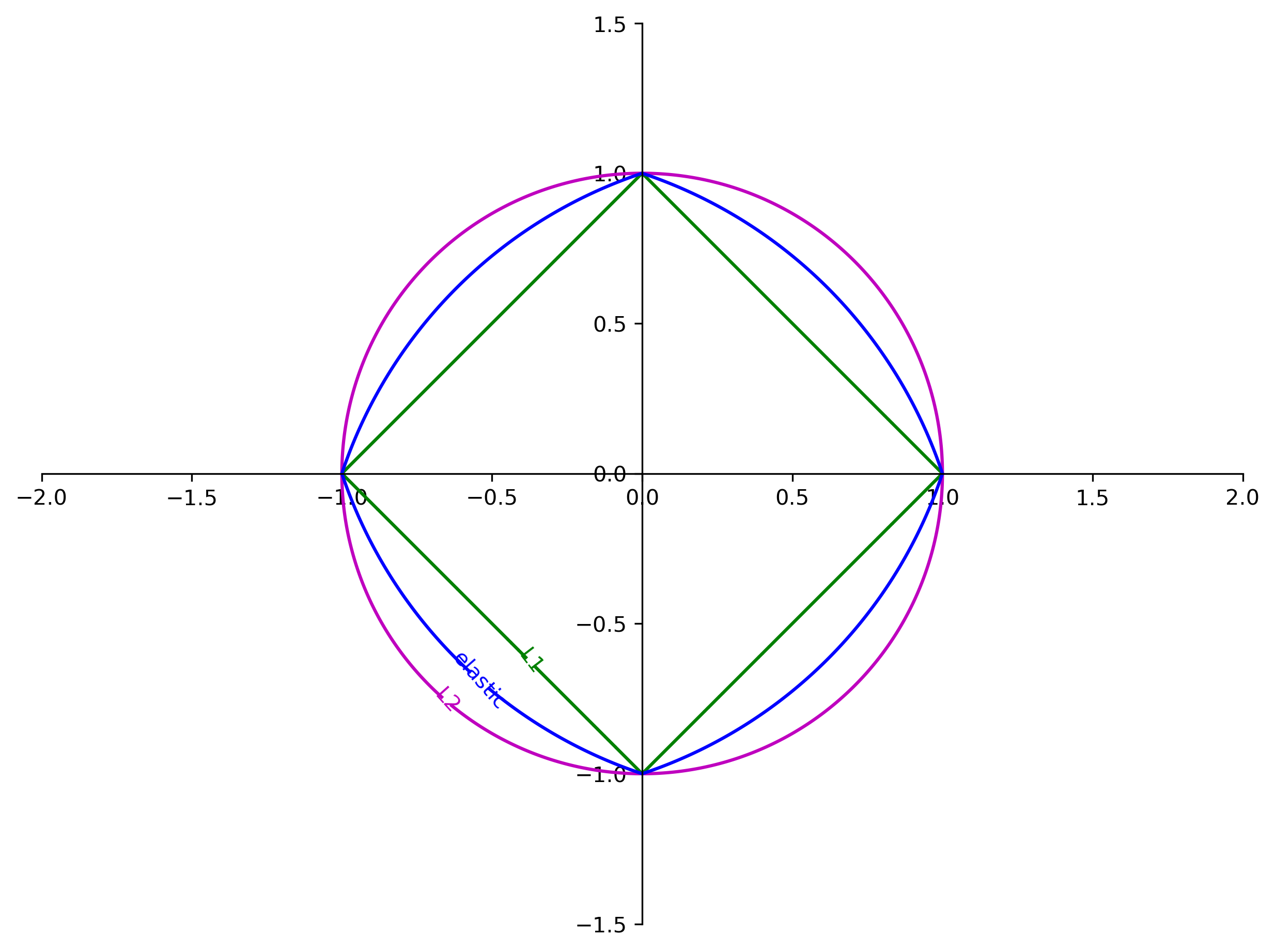

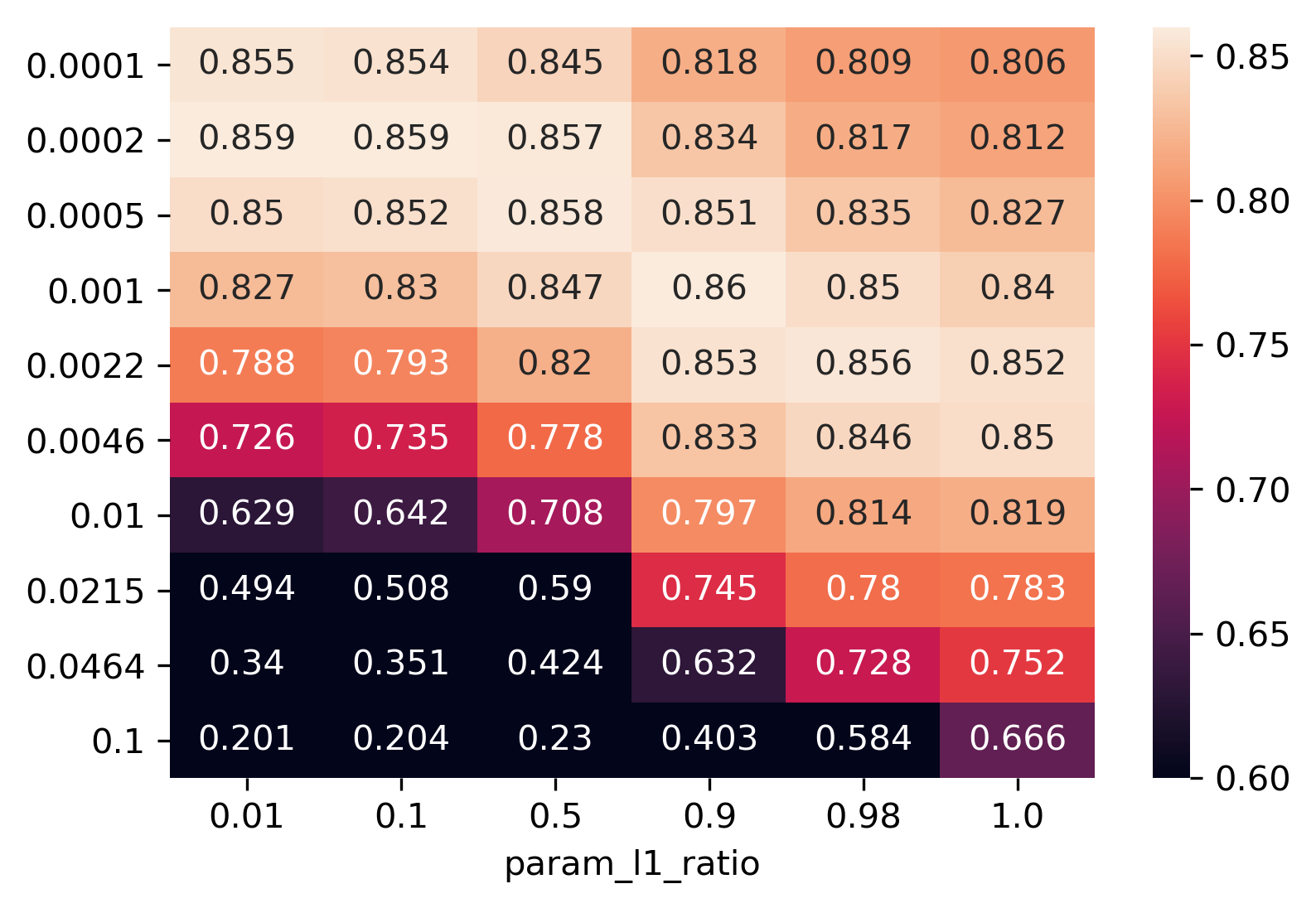

class: center, middle  ### Introduction to Machine learning with scikit-learn # Linear Models for Regression Andreas C. Müller Columbia University, scikit-learn .smaller[https://github.com/amueller/ml-training-intro] --- class:center # Linear Models for Regression  $$\hat{y} = w^T \mathbf{x} + b = \sum_{i=1}^p w_i x_i +b$$ ??? Predictions in all linear models for regression are of the form shown here: It's an inner product of the features with some coefficient or weight vector w, and some bias or intercept b. In other words, the output is a weighted sum of the inputs, possibly with a shift. here i runs over the features and x_i is one feature of the data point x. These models are called linear models because they are linear in the parameters w. The way I wrote it down here they are also linear in the features x_i. However, you can replace the features by any non-linear function of the inputs, and it'll still be a linear model. There are many differnt linear models for regression, and they all share this formula for making predictions. The difference between them is in how they find w and b based on the training data. --- # Ordinary Least Squares $$\hat{y} = w^T \mathbf{x} + b = \sum_{i=1}^p w_i x_i +b $$ `$$\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^p} \sum_{i=1}^p ||w^T\mathbf{x}_i - y_i||^2$$` Unique solution if $\mathbf{X} = (\mathbf{x}_1, ... \mathbf{x}_n)^T$ has full column rank. ??? The most straight-forward solution that goes back to Gauss is ordinary least squares. In ordinary least squares, find w and b such that the predictions on the training set are as accurate as possible according the the squared error. That intuitively makes sense: we want the predictions to be good on the training set. If there is more samples than features (and the samples span the whole feature space), then there is a unique solution. The problem is what's called a least squares problem, which is particularly easy to optimize and get the unique solution to. However, if there are more features than samples, there are usually many perfect solutions that lead to 0 error on the training set. Then it's not clear which solution to pick. Even if there are more samples than features, if there are strong correlations among features the results might be unstable, and we'll see some examples of that soon. Before we look at examples, I want to introduce a popular alternative. --- # Ridge Regression `$$ \min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^p} \sum_{i=1}^n ||w^T\mathbf{x}_i - y_i||^2 + \alpha ||w||^2 $$` Always has a unique solution. Tuning parameter alpha. ??? In Ridge regression we add another term to the optimization problem. Not only do we want to fit the training data well, we also want w to have a small squared l2 norm or squared euclidean norm. The idea here is that we're decreasing the "slope" along each of the feature by pushing the coefficients towards zero. This constraings the model to be more simple. So there are two terms in this optimization problem, which is also called the objective function of the model: the data fitting term here that wants to be close to the training data according to the squared norm, and the prenalty or regularization term here that wants w to have small norm, and that doesn't depend on the data. Usually these two goals are somewhat opposing. If we made w zero, the second term would be zero, but the predictions would be bad. So we need to trade off between these two. The trade off is problem specific and is specified by the user. If we set alpha to zero, we get linear regression, if we set alpha to infinity we get a constant model. Obviously usually we want something in between. This is a very typical example of a general principle in machine learning, called regularized empirical risk minimization. --- # (regularized) Empirical Risk Minimization `$$ min_{f \in F} \sum_{i=1}^n L(f(\mathbf{x}_i), y_i) + \alpha R(f) $$` ??? FIXME pointers data fitting / regularization! Many models in machine learning, like linear models, SVMs and neural networks follow the general framework of empirical risk minimization, which you can see here. We formulate the machine learning problem as an optimization problem over a family of functions. In our case that was the family of linear functions parametrized by w and b. The minimization problem consists of two parts, the data fitting part and the model complexity part. The data fitting part says that the predictions mad eby our functions should be accurate according to some loss L. For our regression problems that was the squared loss. The model complexity part says that we prefer simple models and penalizes complicated f. Most machine learning algorithms can be cast into this, with a particular choice of family of functions f, loss function L and regularizer R. And most of machine learning theory is build around this framework. People proof for differnt choices of F and L and R that if you minimize this, you'll be able to generalize well. And that makes intuitive sense. To do well on the test set, we definitely want to do reasonably well on the training set. We don't expect that we can do better on a test set than the training set. But we also want to minimize the performance difference between training and test set. If we restrict our model to be simple via the regularizer R, we have better chances of the model generalizing. --- # Reminder on model complexity  ??? I hope this sounds familiar from what we talked about last time. This is a particular way of dealing with overfitting and underfitting. For this framework in general, or for ridge regression in particular, trading off the data fitting and the regularization changes the model complexity. If we set alpha high we restrict the model, and we will be on the left side of the graph. If we make alpha small, we allow the model to fit the data more, and we're on the right side of the graph. --- # Boston Housing Dataset  .smaller[ ```python print(X.shape) print(y.shape) ``` ``` (506, 13) (506,) ``` ] ??? Ok after all this pretty abstract talk, let's make this concrete. Let's do some regression on the boston housing dataset. After the last homework you're hopefully familiar with it. The idea is to predict prices of property in the boston area in different neighborhoods. This is a dataset from the 70s I think, so everything is pretty cheap. Most of the features you can see are continuous, with the exception of the charlston river variable which says whether the neighborhood is on the river. Keep in mind that this data lives in a 13 dimensional space and these univariate plots only look at 13 different projections of the data, and can't capture any of the interactions. But still we can see that the price clearly depends on some of these variables. It's also pretty clear that the dependency is non-linear for some of the variables. We'll still start with a linear model, because its a very simple class of models, and I'd always star approaching any model from the simplest baseline. In this case it's linear regression. We're having 506 samples and 13 features. We have much more samples than features. Linear regression should work just fine. Also it's a tiny dataset, so basically anything we'll try will run instantaneously, which is also good to keep in mind. Another thing that you can see in this graph is that the features have very different scales. Here's a box plot that shows that even more clearly. ---  ??? That's something that will trip up the distance based models models we talked about last time, as well as the linear models we're talking about today. For the penalized models the different scales mean that different features are penalized differently, which you usually want to avoid. Usually there is no particular semantics attached to the fact that one feature has different magnitutes than another. We could measure something in inches instead of miles, and that would change the outcome of the model. That's certainly not something we want. A good idea is to scale the data to get rid of this effect. We'll talk about that and other preprocessing methods in-depth on Wednesday next week. Today I'm mostly gonna ignore this. But let's get started with Linear Regression --- class: middle, spacious ```python from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split( X, y, random_state=0) np.mean(cross_val_score(LinearRegression(), X_train, y_train, cv=10)) ``` ``` 0.717 ``` ```python np.mean(cross_val_score(Ridge(), X_train, y_train, cv=10)) ``` ``` 0.715 ``` ??? So here are the --- # Coefficient of determination R^2 `$$ R^2(y, \hat{y}) = 1 - \frac{\sum_{i=0}^{n - 1} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{\sum_{i=0}^{n - 1} (y_i - \bar{y})^2} $$` `$$ \bar{y} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=0}^{n - 1} y_i$$` Can be negative for biased estimators - or the test set! ??? --- # Scaling (if you want) ```python from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler X, y = boston.data, boston.target X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, random_state=0) scaler = StandardScaler() scaler.fit(X_train) X_train_scaled = scaler.transform(X_train) ridge = Ridge().fit(X_train_scaled, y_train) X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test) ridge.score(X_test_scaled, y_test) ``` ??? If you want to scale the data, you can use StandardScaler for that. It makes the mean zero and the standard deviation one. It's an unsupervised model, so it only takes the data X_train to fit. Fitting just means computing mean and standard devitation. Then, we can scale the data using the transform method. Make sure that you fit the data only on the training set, and then transform the training and the test set. If you want to use scaling inside cross-validation, it's a little bit more tricky. As I said, more details next wednesday. I'm just mentioning this here because it might come in handy for the homework. Ok but so let's come back to the Ridge model. Above we just used the default setting for the parameter alpha, which is one. This is a reasonable default, but there is no reason why this should give us the optimum generalization performance on this problem. So it's a good idea to adjust the parameter. As we saw on Monday, we can easily do that with gridsearchCV. --- .smallest[ ```python from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV param_grid = {'alpha': np.logspace(-3, 3, 13)} print(param_grid) ``` ``` {'alpha': array([ 0.001, 0.003, 0.01, 0.032, 0.1, 0.316, 1., 3.162, 10., 31.623, 100., 316.228, 1000.])} ``` ```python grid = GridSearchCV(Ridge(), param_grid, cv=10) grid.fit(X_train, y_train) ``` ] .center[  ] ??? --- # Adding features ```python from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures, scale poly = PolynomialFeatures(include_bias=False) X_poly = poly.fit_transform(scale(X)) print(X_poly.shape) X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X_poly, y) ``` ``` (506, 104) ``` ```python np.mean(cross_val_score(LinearRegression(), X_train, y_train, cv=10)) ``` ``` 0.74 ``` ```python np.mean(cross_val_score(Ridge(), X_train, y_train, cv=10)) ``` ``` 0.76 ``` ??? --- .center[  ] .smaller[ ```python print(grid.best_params_) print(grid.best_score_) ``` ``` {'alpha': 31.6} 0.83 ``` ] ??? --- # Plotting coefficient values (LR) ```python lr = LinearRegression().fit(X_train, y_train) plt.scatter(range(X_poly.shape[1]), lr.coef_, c=np.sign(lr.coef_), cmap="bwr_r") ``` .center[  ] ??? --- # Ridge Coefficients ```python ridge = grid.best_estimator_ plt.scatter(range(X_poly.shape[1]), ridge.coef_, c=np.sign(ridge.coef_), cmap="bwr_r") ``` .center[  ] ??? --- ```python ridge100 = Ridge(alpha=100).fit(X_train, y_train) ridge1 = Ridge(alpha=1).fit(X_train, y_train) plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4)) plt.plot(ridge1.coef_, 'o', label="alpha=1") plt.plot(ridge.coef_, 'o', label="alpha=14") plt.plot(ridge100.coef_, 'o', label="alpha=100") plt.legend() ``` .center[  ] ??? --- # Coefficient Paths  ??? --- # Learning Curves  ??? --- # Lasso Regression `$$ \min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^p} \sum_{i=1}^n ||w^T\mathbf{x}_i - y_i||^2 + \alpha ||w||_1 $$` - Shrinks w towards zero like Ridge - Sets some w exactly to zero - automatic feature selection! ??? --- # Understanding L1 and L2 Penalties .wide-left-column[  ] .narrow-right-column[ .smaller[ `$$ \ell_2(w) = \sum_i \sqrt{w_i ^ 2}$$` `$$ \ell_1(w) = \sum_i |w_i|$$` `$$ \ell_0(w) = \sum_i 1_{w_i != 0}$$` ]] ??? --- # Understanding L1 and L2 Penalties .wide-left-column[  ] .narrow-right-column[ .padding-top[ .smaller[ `$ f(x) = (2 x - 1)^2 $` `$ f(x) + L2 = (2 x - 1)^2 + \alpha x^2$` `$ f(x) + L1= (2 x - 1)^2 + \alpha |x|$` ]]] ??? --- class: center # Understanding L1 and L2 Penalties  ??? --- class: center # Understanding L1 and L2 Penalties  ??? --- # Grid-Search for Lasso ```python param_grid = {'alpha': np.logspace(-3, 0, 13)} print(param_grid) ``` ``` {'alpha': array([ 0.001, 0.003, 0.01, 0.032, 0.1, 0.316, 1., 3.162, 10., 31.623, 100., 316.228, 1000.])} ``` ```python grid = GridSearchCV(Lasso(normalize=True), param_grid, cv=10) grid.fit(X_train, y_train) print(grid.best_params_) print(grid.best_score_) ``` ``` {'alpha': 0.001} 0.837 ``` ??? ---  ??? --- .center[  ] ```python print(X_poly.shape) np.sum(lasso.coef_ != 0) ``` ``` (506, 104) 64 ``` ??? --- .smaller[ ```python from sklearn.linear_model import lars_path # lars_path computes the exact regularization path which is piecewise linear. X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, random_state=42) alphas, active, coefs = lars_path(X_train, y_train, eps=0.00001, method="lasso") plt.plot(alphas, coefs.T, alpha=.5) plt.xscale("log") ``` ] .center[  ] ??? --- # Elastic Net - Combines benefits of Ridge and Lasso - two parameters to tune. `$$\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^p} \sum_{i=1}^n ||w^T\mathbf{x}_i - y_i||^2 + \alpha_1 ||w||_1 + \alpha_2 ||w||^2_2 $$` ??? --- class: center # Comparing unit balls  ??? --- # Parametrization in scikit-learn `$$\min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^p} \sum_{i=1}^n ||w^T\mathbf{x}_i - y_i||^2 + \alpha \eta ||w||_1 + \alpha (1 - \eta) ||w||^2_2 $$` Where $\eta$ is the relative amount of l1 penalty (`l1_ratio` in the code). ??? --- # Grid-searching ElasticNet ```python from sklearn.linear_model import ElasticNet param_grid = {'alpha': np.logspace(-4, -1, 10), 'l1_ratio': [0.01, .1, .5, .9, .98, 1]} grid = GridSearchCV(ElasticNet(), param_grid, cv=10) grid.fit(X_train, y_train) print(grid.best_params_) print(grid.best_score_) ``` ``` {'alpha': 0.0001, 'l1_ratio': 0.01} 0.718 ``` --- class: smaller # Analyzing grid-search results ```python import pandas as pd res = pd.pivot_table(pd.DataFrame(grid.cv_results_), values='mean_test_score', index='param_alpha', columns='param_l1_ratio') ``` .center[  ]