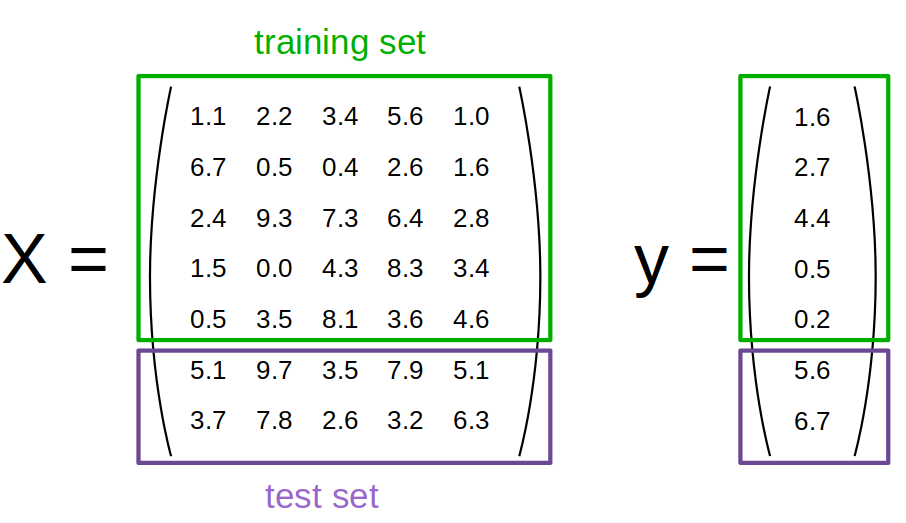

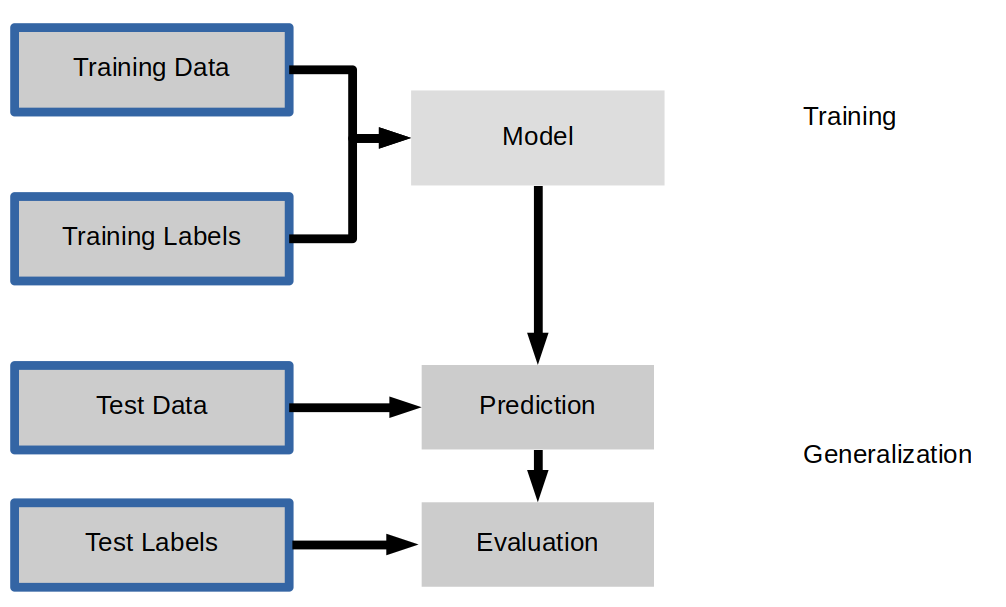

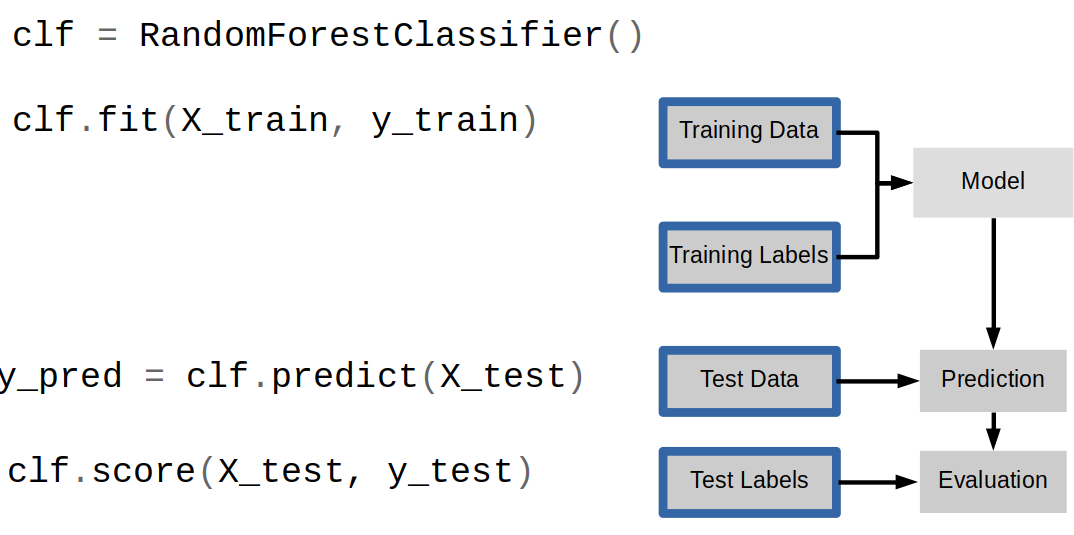

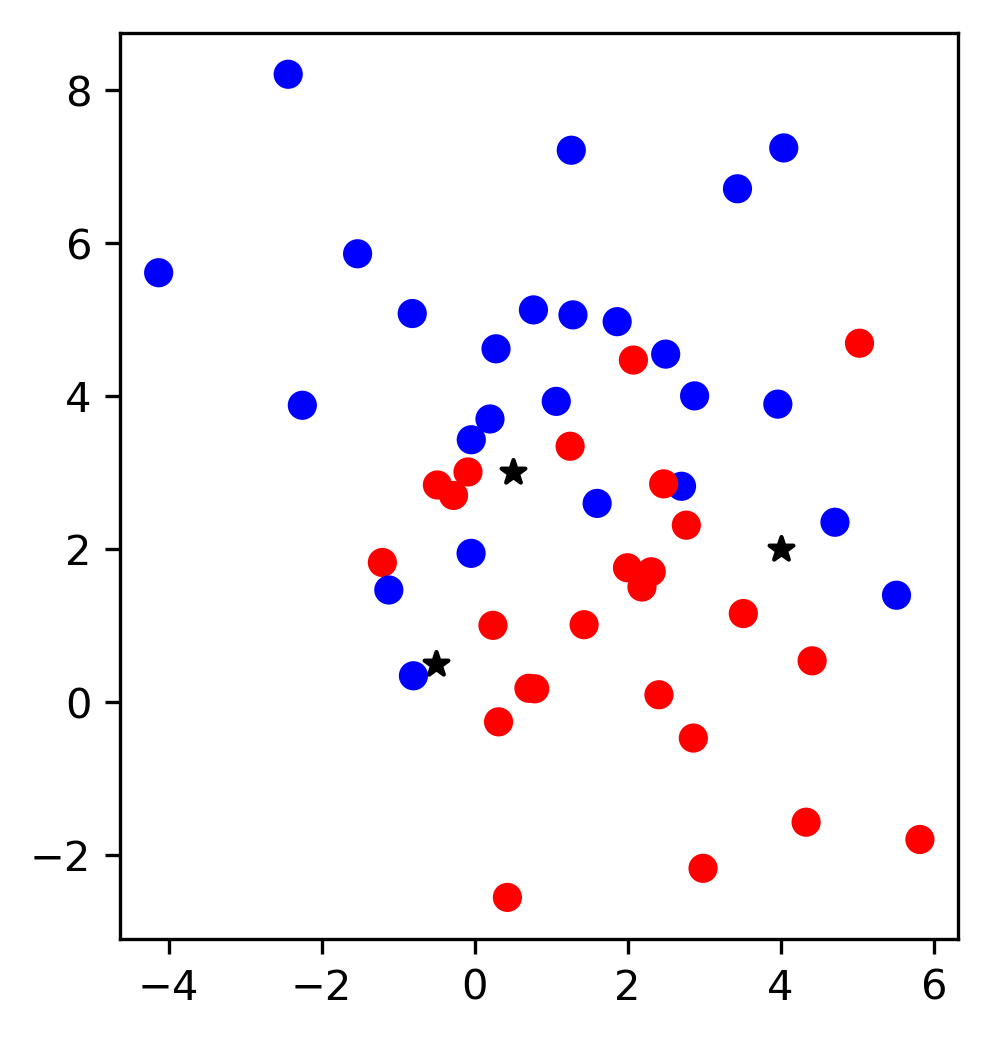

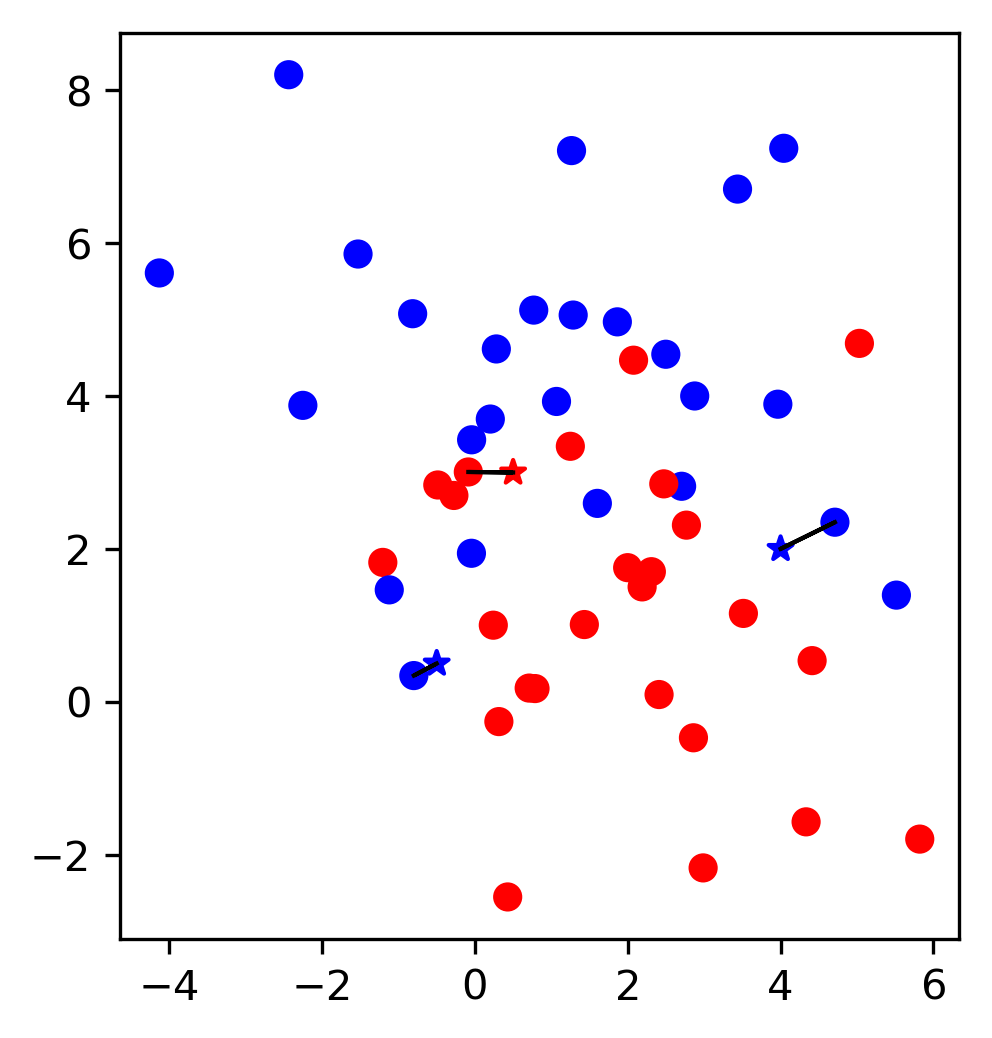

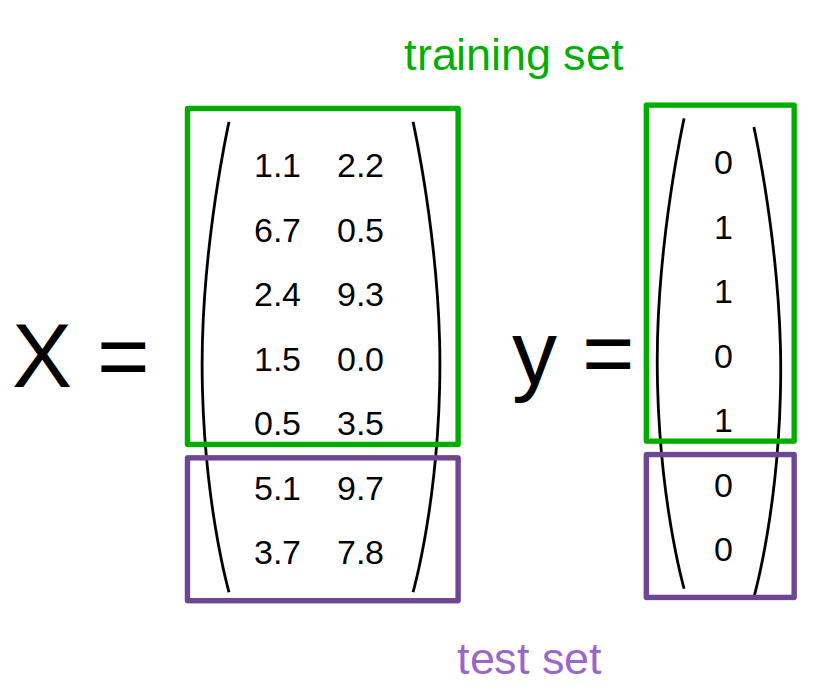

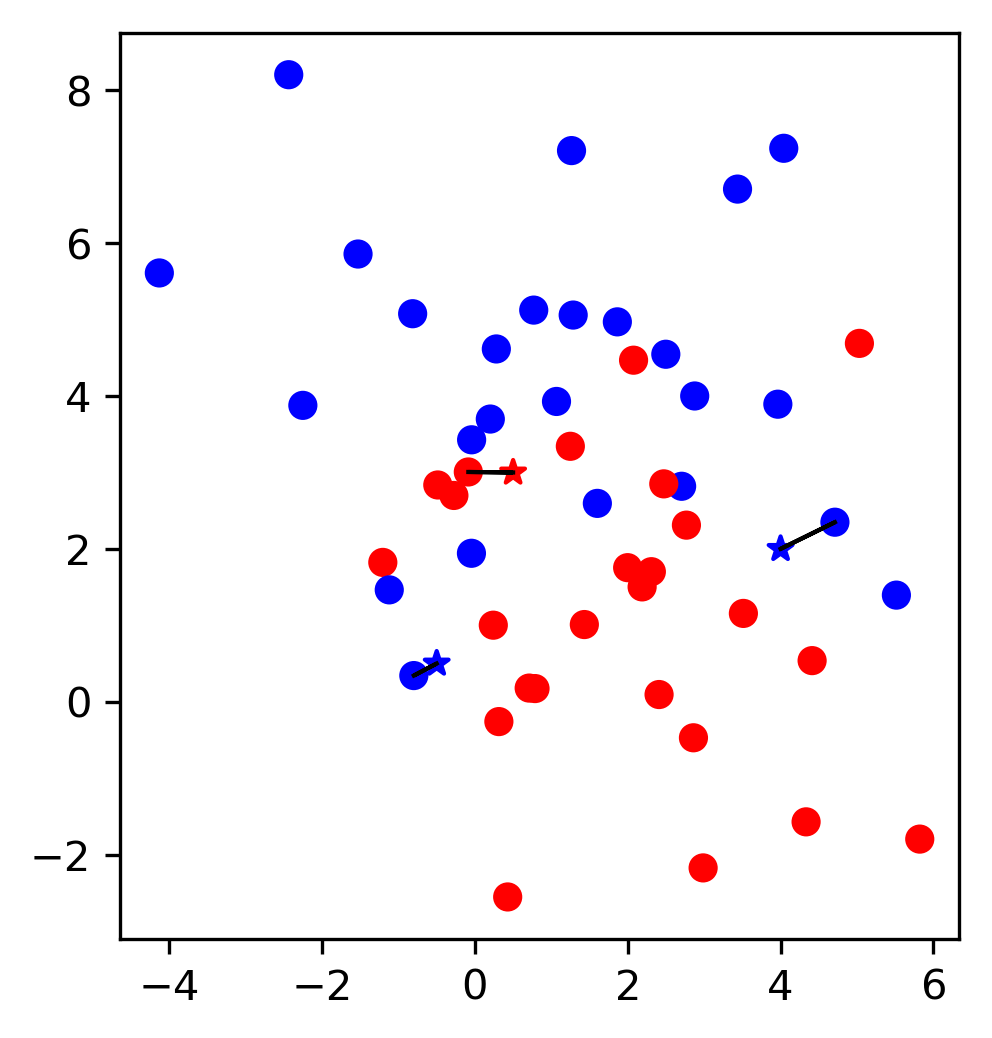

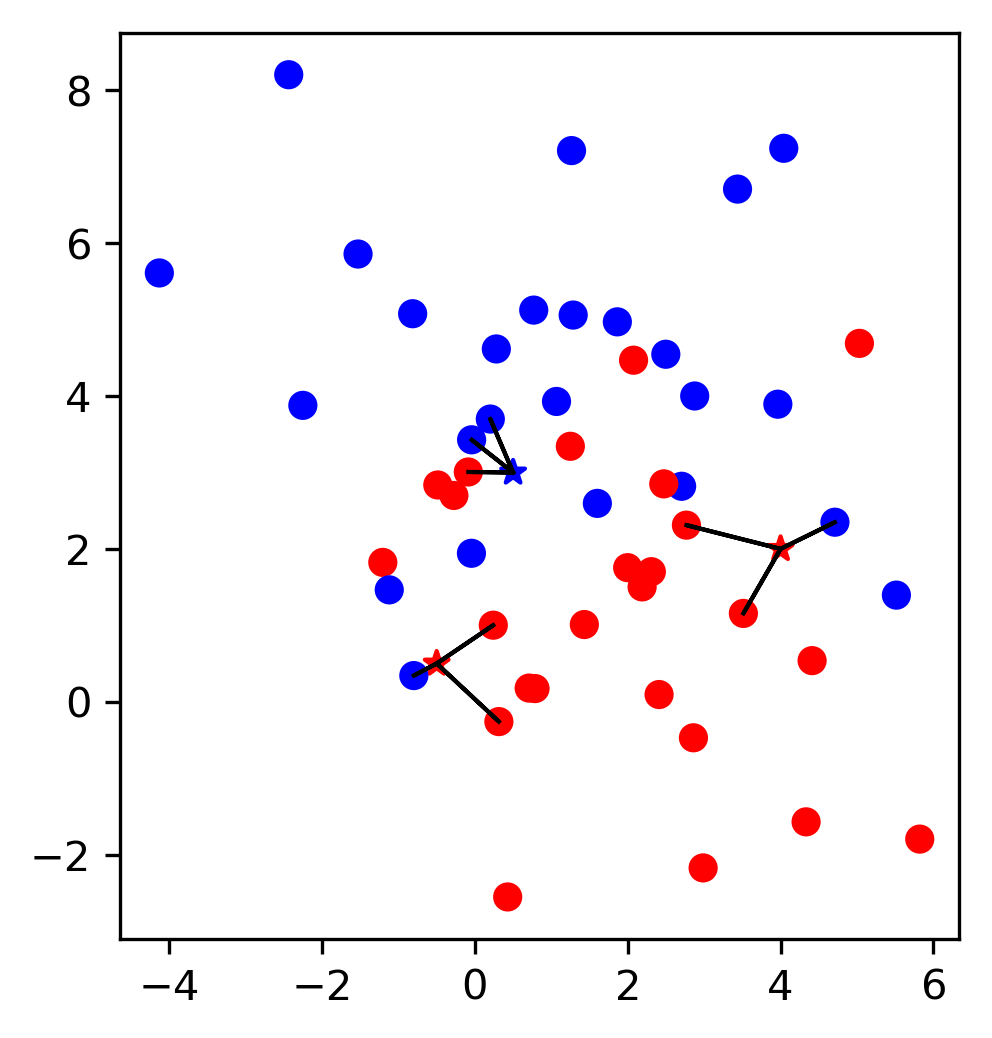

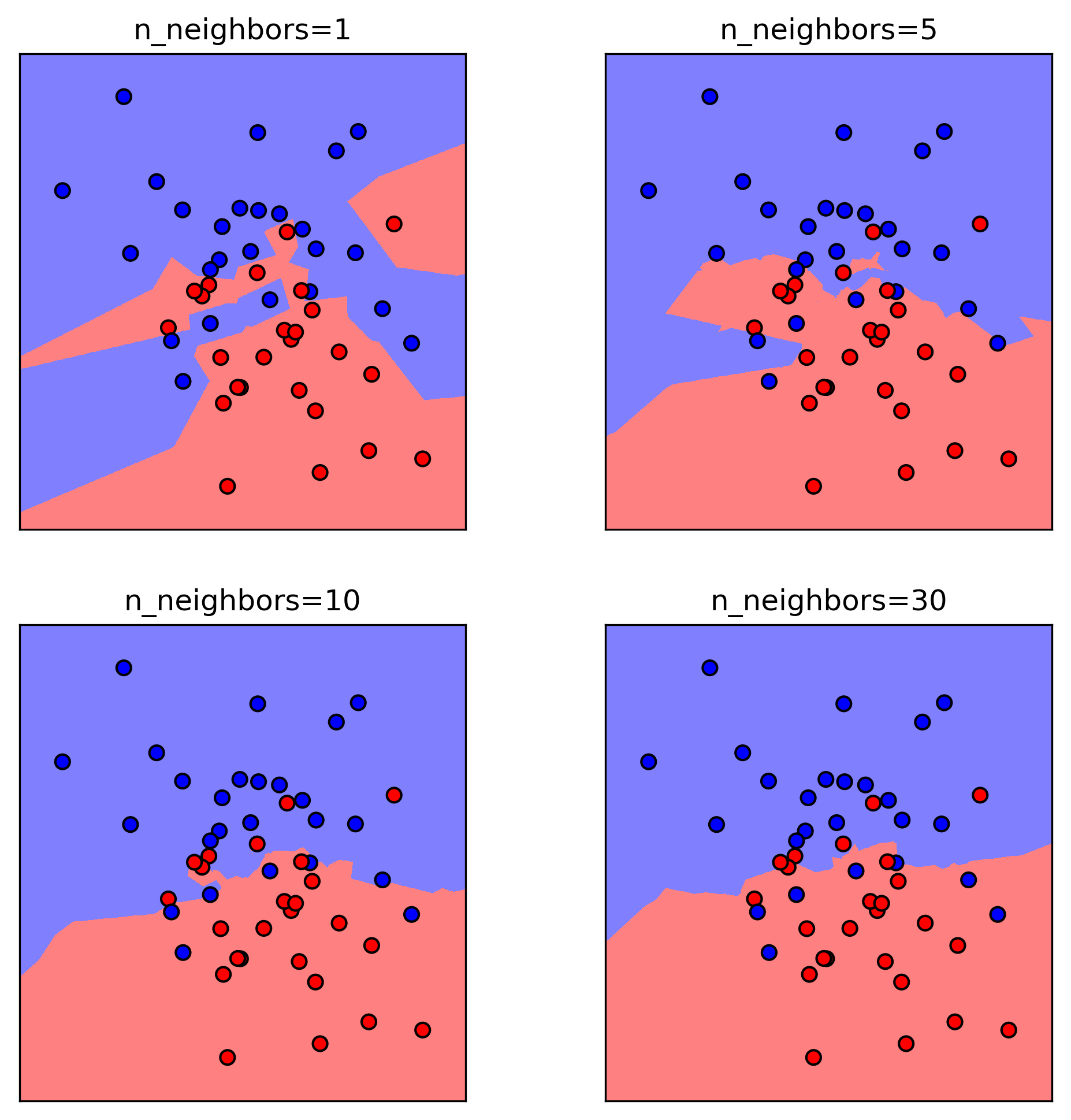

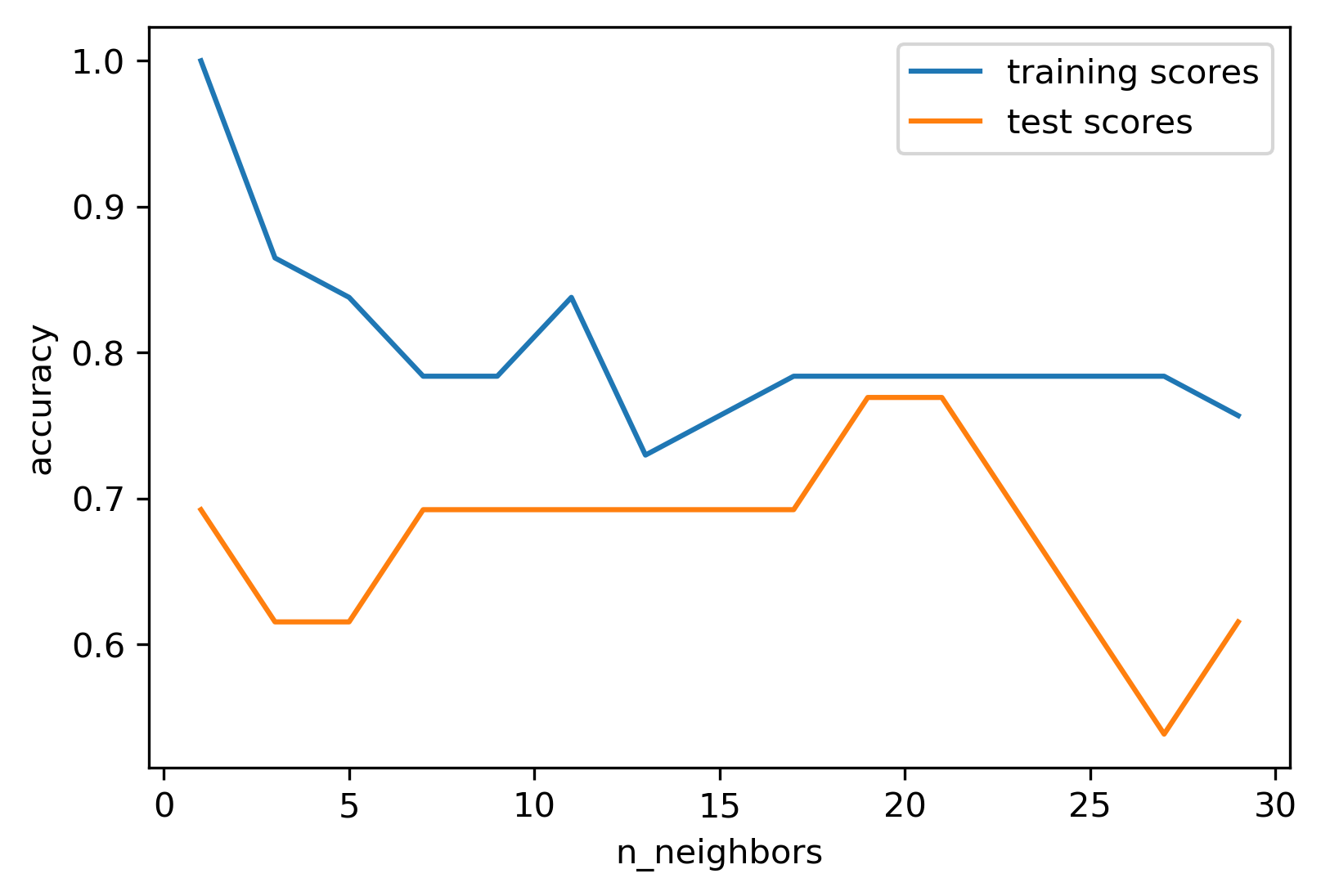

class: center, middle  ### Introduction to Machine learning with scikit-learn # Supervised Learning Andreas C. Müller Columbia University, scikit-learn .smaller[https://github.com/amueller/ml-workshop-1-of-4] --- class: center # scikit-learn documentation  <a href="http://scikit-learn.org/" style="color:black; font-size:50px; text-decoration:None" >scikit-learn.org</a> --- class: center # Representing Data  --- class: center # Training and Test Data  --- class: center, middle # Notebook: Data Loading --- class: center # Supervised ML Workflow  --- class: center # Supervised ML Workflow  --- class: center # Nearest Neighbors  $$f(x) = y_i, i = \text{argmin}_j || x_j - x||$$ ??? Let’s say we have this two-class classification dataset here, with two features, one on the x axis and one on the y axis. And we have three new points as marked by the stars here. If I make a prediction using a one nearest neighbor classifier, what will it predict? It will predict the label of the closest data point in the training set. That is basically the simplest machine learning algorithm I can come up with. Here’s the formula: the prediction for a new x is the y_i so that x_i is the closest point in the training set. Ok, so now how do we find out whether this model is any good? --- class: center # Nearest Neighbors  $$f(x) = y_i, i = \text{argmin}_j || x_j - x||$$ ??? Let’s say we have this two-class classification dataset here, with two features, one on the x axis and one on the y axis. And we have three new points as marked by the stars here. If I make a prediction using a one nearest neighbor classifier, what will it predict? It will predict the label of the closest data point in the training set. That is basically the simplest machine learning algorithm you can think of. Here’s the formula: the prediction for a new x is the y_i so that x_i is the closest point in the training set. Ok, so now how do we find out whether this model and these predictions are any good? --- class: center  ??? The simplest way is to split the data into a training and a test set. So we take some part of the data set, let’s say 75% and the corresponding output, and train the model, and then apply the model on the remaining 25% to compute the accuracy. This test-set accuracy will provide an unbiased estimate of future performance. So if our i.i.d. assumption is correct, and we get a 90% success rate on the test data, we expect about a 90% success rate on any future data, for which we don't have labels. Let's dive into how to build and evaluate this model with scikit-learn. --- # KNN with scikit-learn ```python from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y) from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=1) knn.fit(X_train, y_train) print("accuracy: ", knn.score(X_test, y_test))) y_pred = knn.predict(X_test) ``` accuracy: 0.77 ??? We import train_test_split form model selection, which does a random split into 75%/25%. We provide it with the data X, which are our two features, and the labels y. As you might already know, all the models in scikit-learn are implemented in python classes, with a single object used to build and store the model. We start by importing our model, the KneighborsClassifier, and instantiate it with n_neighbors=1. Instantiating the object is when we set any hyper parameter, such as here saying that we only want to look at the neirest neighbor. Then we can call the fit method to build the model, here knn.fit(X_train, y_train) All models in scikit-learn have a fit-method, and all the supervised ones take the data X and the outcomes y. The fit method builds the model and stores any estimated quantities in the model object, here knn. In the case of nearest neighbors, the `fit` methods simply remembers the whole training set. Then, we can use knn.score to make predictions on the test data, and compare them against the true labels y_test. For classification models, the score method will always compute accuracy. Just for illustration purposes, I also call the predict method here. The predict method is what's used to make predictions on any dataset. If we use the score method, it calls predict internally and then compares the outcome to the ground truth that's provided. Who here has not seen this before? --- class: center # Influence of Number of Neighbors  ??? So this was the predictions as made by one-nearest neighbor. But we can also consider more neighbors, for example three. Here is the three nearest neighbors for each of the points and the corresponding labels. We can then make a prediction by considering the majority among these three neighbors. And as you can see, in this case all the points changed their labels! (I was actually quite surprised when I saw that, I just picked some points at random). Clearly the number of neighbors that we consider matters a lot. But what is the right number? The is a problem you’ll encounter a lot in machine learning, the problem of tuning parameters of the model, also called hyper-parameters, which can not be learned directly from the data. --- class: center # Influence of Number of Neighbors  ??? So this was the predictions as made by one-nearest neighbor. But we can also consider more neighbors, for example three. Here is the three nearest neighbors for each of the points and the corresponding labels. We can then make a prediction by considering the majority among these three neighbors. And as you can see, in this case all the points changed their labels! (I was actually quite surprised when I saw that, I just picked some points at random). Clearly the number of neighbors that we consider matters a lot. But what is the right number? The is a problem you’ll encounter a lot in machine learning, the problem of tuning parameters of the model, also called hyper-parameters, which can not be learned directly from the data. --- class: center, some-space # Influence of n_neighbors  ??? Here’s an overview of how the classification changes if we consider different numbers of neighbors. You can see as red and blue circles the training data. And the background is colored according to which class a datapoint would be assigned to for each location. For one neighbor, you can see that each point in the training set has a little area around it that would be classified according to it’s label. This means all the training points would be classified correctly, but it leads to a very complex shape of the decision boundary. If we increase the number of neighbors, the boundary between red and blue simplifies, and with 40 neighbors we mostly end up with a line. This also means that now many of the training data points would be labeled incorrectly. --- class: center, spacious # Model complexity  ??? We can look at this in more detail by comparing training and test set scores for the different numbers of neighbors. Here, I did a random 75%/25% split again. This is a very noisy plot as the dataset is very small and I only did a random split, but you can see a trend here. You can see that for a single neighbor, the training score is 1 so perfect accuracy, but the test score is only 70%. If we increase the number of neighbors we consider, the training score goes down, but the test score goes up, with an optimum at 19 and 21, but then both go down again. This is a very typical behavior, that I sketched in a schematic for you. --- class: center, middle # Notebook: Supervised Learning